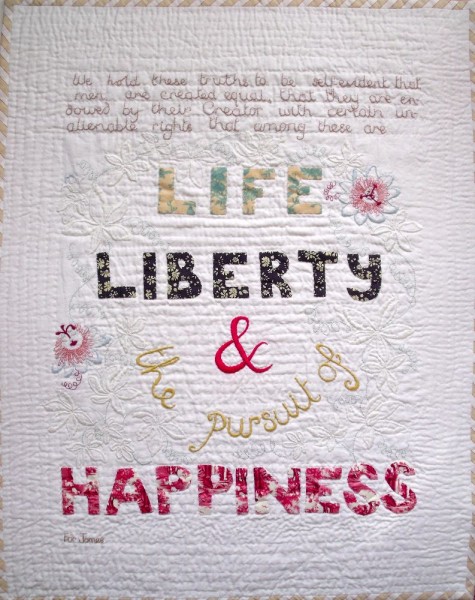

Text taken from the Declaration of Independence. Embroidery cottons and silks on linen with appliqued floral cottons.

This hanging was made as a Christmas present for my son-in-law, a political journalist, who thought these words would be the ones he would be happiest to have hanging on his wall. He also had them hanging in his wedding reception’s marquee (see below) and I hope he was also happy about that, although, I have to admit – from this distance of nearly a year ago – that I’m not sure that he was ever consulted on the matter.

As the text at the top of the photograph is not clearly legible, here it is , “We hold these truths to be self evident, that men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. On the suggestion of John Adams, the text of the declaration was originally drafted by Jefferson and edited by the Congress. This is the final version.

I really wanted to embroider passionflowers and to justify doing so, I delved into all sorts of books and internet sites looking for a reference to one of the frontline founding fathers having grown them. Eventually I found a reference to Jefferson having grown passionflowers in his garden at Monticello and , as I thought, photocopied or printed out the relevant pages. Now, a year later, I tried to find the relevant sheets or the notes I thought I’d made on them but I have to admit I have been utterly thwarted.

So, in general terms there are 9 species of Passiflora native to the USA while, curiously, there are none that are native to Africa. Although Jefferson went through experimental phases of testing all sorts of exotic seeds, in the end he became most energised about indigenous plants and for this reason it seems likely to me that he would have had some of the glorious native species of Passiflora climbing up one or two of the many trees or tumbling over walls in in his plantsman’s garden. I realise that it probably would not have been P.caerulea, the one I have used in my embroidery, as this is the commonest variety to be seen in the milder parts of the UK. The most prolific species in the south-eastern states of the US is P.incarnata (aka maypops) which is v. similar to P.caerulea, both being bluish-white, although the former can be purple and has a longer fringed corona, longer and more prominent styles and more pronounced stamens. The edible fruit of the former is known in the US as maypops which ripens to an orange colour and is the size of a hen’s egg.

Now I come to think about it, the purple flower might have been a better choice for my hanging, making more of an impact on the white linen.

This year I have done more reading about America’s Founding Fathers and discovered that, in the case of Franklin, Jefferson, Washington, Madison and John Adams, it is impossible detach their fascination with horticulture from their political ideology. Andrea Wulf’s 2011 book, “The Founding Gardeners” (How the Revolutionary Generation Created an American Eden) views America’s political history through this lens, convincing the reader that farming and gardening were no mere hobby interests but the most important areas of study for these men of the enlightenment as they set about creating a new and independent nation.

For Franklin, agriculture was the only honest way for a nation to acquire wealth (“Positions to be examined concerning National Wealth”, 1769). During diplomatic missions to Europe he met people with similar botanical interests and sent seeds back home across the Atlantic so that the economic potential of every new edible plant that he came across could be evaluated in home soil. New kinds of oats ,and barley from were sent to his wife Deborah to distribute among the plantsmen in Philadelphia, along with Chinese rhubarb which was to be evaluated for its curative properties

Washington, after success in battle, was offered almost dictatorial powers which horrified him. After 2 terms as president, he chose life as a farmer and plantsman and from then on was often called ‘the Cincinnatus of the West’, after the Roman hero who left his plough to serve his country and then returned to the plough after his victory. Since first being settled, Virginia had grown little else other than tobacco for British merchants. Washington was anxious to repair the two-fold damage of this policy. Not only had monoculture exhausted the soil but it had led to Virginia being too dependent upon Britain and the vagaries of prices set thousands of miles away. Ever innovative, Washington experimented spreading his fields with things like gypsum, marl, ash and fish heads and entrails before settling on manure. For the first American president, the country’s future lay in restoring field fertility and evaluating the hidden secrets of native forests.

Adams’s estate was much the smallest of those considered here but he, too saw problems in the relationship with Britain’s colonial power. As Humphfrey Ploughjogger, he wrote columns in a Boston newspaper urging his fellow colonists to turn their backs on British goods, wear clothes made from local animal hides, not British wool, and eat only what they could grow themselves. He championed the kitchen garden and when on diplomatic missions to Europe his letters to and from his wife Abigail are full of horticultural concerns. He was fond of informing his political thinking by practical experience gained from farm work. The need for political checks and balances was compared to the humble knowledge of a farmhand, that to drive a wagon down a steep hill you put one pair of oxen in front and one pair behind to counterbalance one power by another.

Jefferson had his head completely turned by European agriculture and gardens when first he went to Europe. He visited gardens and farms with enthusiasm and sent vast numbers of seeds back to Monticello for planting in his experimental beds. French scientists had noted that many of these exotic species did not thrive in America and this had led to a French theory of the degeneracy of America – some even maintained that transplanted humans didn’t do as well in America either. Jefferson was keen to prove how wrong this was and with this in mind, he wrote ‘Notes on the State of Virginia’ (1785) which was a description of the diversity and munificence of North America’s flora and fauna. Almost 20 years later he was to celebrate finalising the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon which doubled the size of the new country in the stroke of the pen and with it offered the prospect of the discovery of unimaginable new species with the potential for economic wealth. To this end Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark on an expedition West, through the newly bought land and beyond as far as they could go. Their aim was to catalogue the botanical and zoological wonders they encountered en route, to send back specimens of new flora and fauna (alive and dead) and to discover all they could about the natives tribes. After adventures crossing the Rockies they descended to the western edge of the continent, their reports exciting those in the eastern states who were astounded at the breadth of the continent on whose edge they perched.

But for Andrea Wulf researching her book one of the things that surprised her most was that, in 1818, Madison was urging the protection of the environment. For him, the very survival of the United States depended upon respect for the land. He feared forests were being cut down for short term gain, that the already denatured soil was not receiving the attention required for continued fertility and that things were out of equilibrium. Man must find a way to live with nature without destroying it – prescient words from a man bewigged, frock-coated and stiff collared and born in the eighteenth century.

I have been very brief in my notes above, tantalising with snippets. I hope I will send a few people excited to Andrea Wulf’s book, which is a fascinating read for students of politics and horticulture alike. I also recommend the dvd John Adams (2008, mini-series) based on the book of the same name by David McCullough. Watched in tandem with reading the book, each enlightens the other. (You can read criticisms of the dvd afterwards as they are helpfully informative about the bits the biopic gets wrong – whether intentionally for dramatic effect or not ; they don’t really spoil your enjoyment of the dramatisation.)

Finally, I can’t help but end as both the book and the mini-series do. Curiously and memorably, both Adams and Jefferson died 5o years after the Declaration of Independence on the 4th of July. Exactly 5 years later, James Monroe died. Adams was the second President of the United States of America, Jefferson was the third and Monroe was the fifth.

2 Trackbacks

[…] standing for Heaven and purity respectively. I made a hanging for my son-in-law to celebrate ‘Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ from the American Declaration of Independence and used passionflowers as decoration. I now have […]

[…] Wulf’s two excellent books on American gardeners The Founding Gardeners and The Brother Gardeners are remarkable for containing no mention of Hosack. Wulf herself has praised Victoria […]