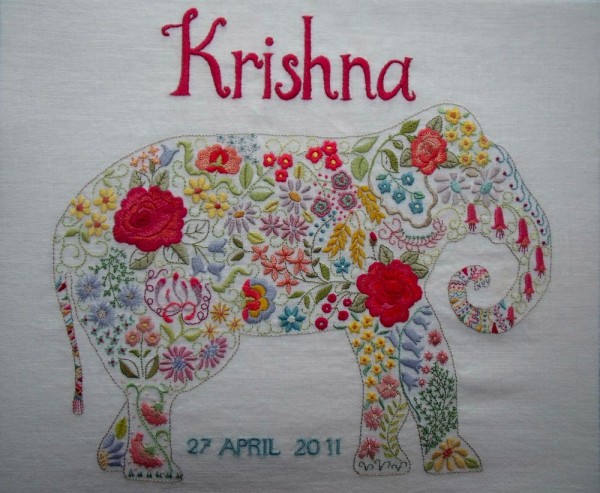

Elephants have always been my eldest daughter’s favourite animals, so when two of her friends had a baby and called her Krishna, there was little doubt that I would be embroidering an elephant to celebrate Krishna’s arrival. Being insufficiently knowledgeable about the Hindu pantheon, I was confused as I had thought that Ganesha was the elephant god and that Krishna was the boy god depicted playing a flute whose skin was often a memorable bright blue.

Emails went to and fro to the parents in California about the finer points of Hindu culture and we learned that yes, typically it is a boy’s name in India as a whole, but that in certain parts of southern India it has a long tradition as a girl’s name. Krishna is also the name of one of the most important rivers in central southern India and in Hindu mythology it is no surprise that rivers are regarded as having a female character .

The key to understanding the name goes back to its Sanskrit origins, where ‘krsna’ is a feminine noun meaning night/ blackness/darkness,with connotations of ‘the dark and beautiful one’, ‘encompassing the night’ and ‘encompassing all attractive qualities’. Baby Krishna’s family view the bearer of the name as being a strong person, with characteristics similar to that of the Goddess Durga who is worshipped in the North and in West Bengal and who is considered as the fiery maintainer of righteousness and moral order. Krishna’s name draws on the memory of her namesake, her maternal great, great grandmother, who is remembered for her beauty, strength of character and independence of thought. She inspired the women of her family to think for themselves and to strive to become role models in whatever they did and she is obviously remembered with considerable affection.

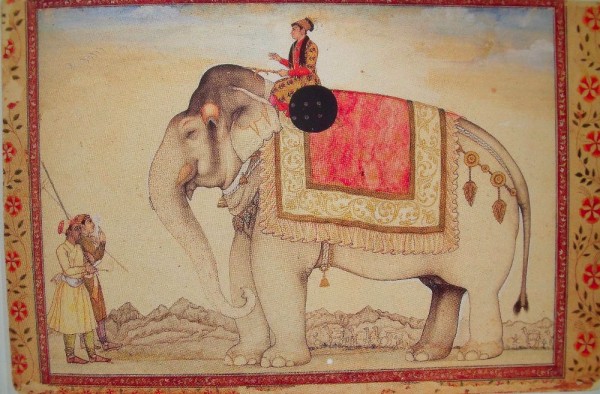

Earlier this year, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford exhibited Howard Hodgkin’s collection of Indian paintings and drawings of the Mughal period (c.1560-1850). Elephants, as the catalogue says, were “a particular Hodgkin predilection”. Hodgkin was no dry, academic collector, his criterion was that a work should quite simply deliver a “shock to the heart” and very often it was the paintings with elephants in them that did this. In his introduction to the catalogue, Andrew Topsfield points out that in paintings where the human figure is stiffly conventional, the elephant is rarely listless or lacking in character. “From earliest times, Indian painters and sculptors have known how to convey a warmly sympathetic sense of this royal animal’s massive volumes, its grace in motion, its noble intelligence and playful charm.”. Here are a few of those paintings from the catalogue “Visions of Mughal India: The collection of Howard Hodgkin”.

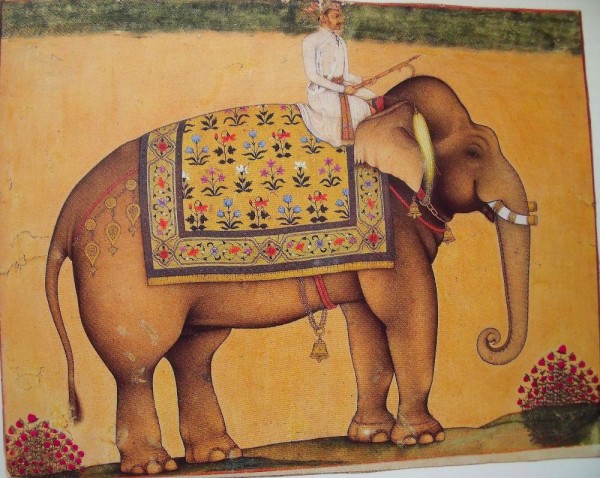

An imperial elephant stands for his portrait with a saddlecloth decorated with stylised flowers in the Mughal style .

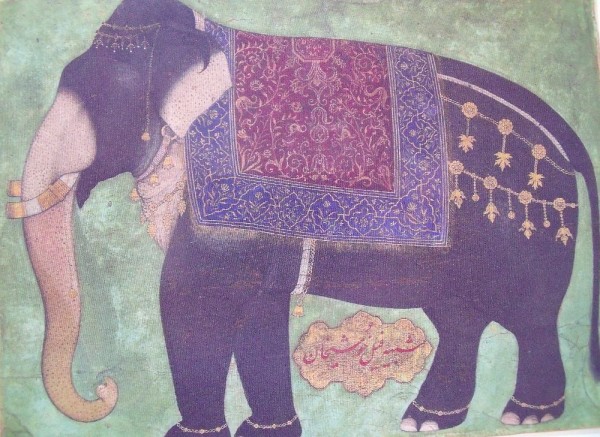

The elephant Khushi Khan

Mughal, c. 1650

Gouache with gold on paper, 26.2 x 35.3 cm

Howard Hodgkin Collection

The elephant Khushi Khan (Lord of Happiness) stands quietly for his portrait and has no need of a mahout to keep him in control. His dark skin and the contrasting mottled rosy pink of the trunk, neck and ear tips were seen as attributes of great beauty. Like bicycles, elephants sported bells to warn others of their presence. “When an elephant runs, or merely walks, he does not stop like a horse would”. (Edgerton, 1931.)

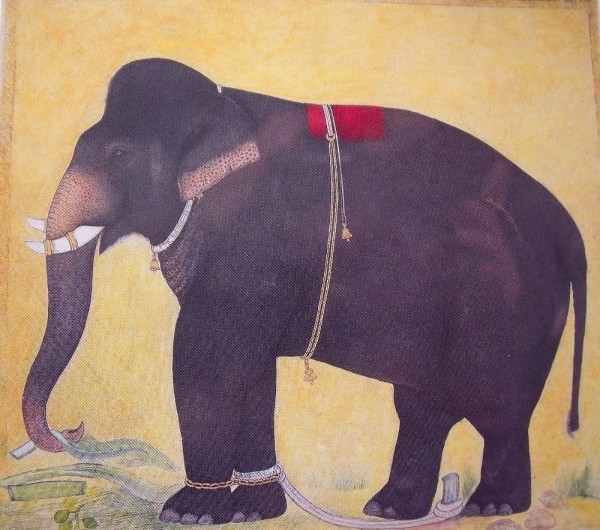

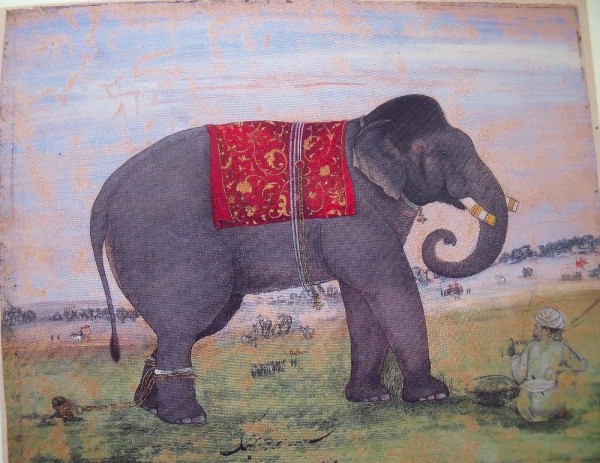

Another beautiful elephant with fine pink mottling. Though off duty he still wears little bells; chains suggest he my still have some youthful exuberance and unpredictability. His diet consists of plantain and banyan leaes as well as sugar cane. Three compact dung balls suggest he has a healthy digestion.

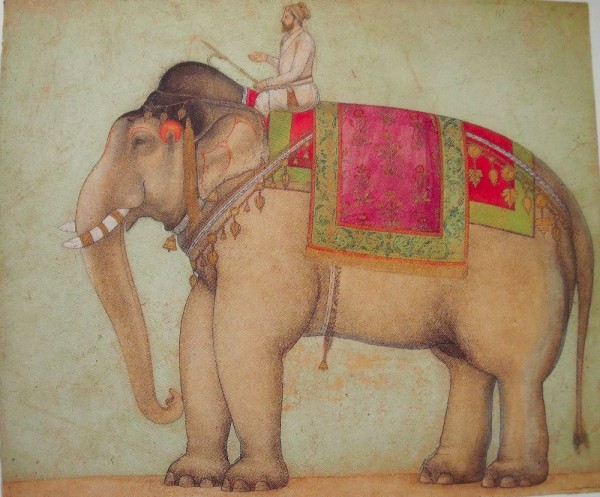

An elephant and keeper

Mughal, c. 1650-60

Gouache with gold on paper, 18 x 22 cm

Howard Hodgkin Collection

A keeper prepares sugar cane for this imperial elephant close to a Mughal army encampment. Both the name of the artist and that of the elephant are now illegible but the hand is very like that of Shah Jahan. The elephant is thought to be Firuz Jang which means Victorious in War.

The difference in scale of mahout to elephant symbolises the importance of this grand elephant, whose body is decorated with orange patterning indicating a festive occasion. In his hand the mahout lightly holds an ankus.

This elephant is named after the Hindu elephant-headed god and he stands quietly dignified and calm. At some point he has lost a tusk. Aurangzeb waged many campaigns in the Deccan and it may be that the rider is one of his sons. The two men on the left are keepers, identified because they carry charkhis, or poles with firework attachments for restraining elephants.

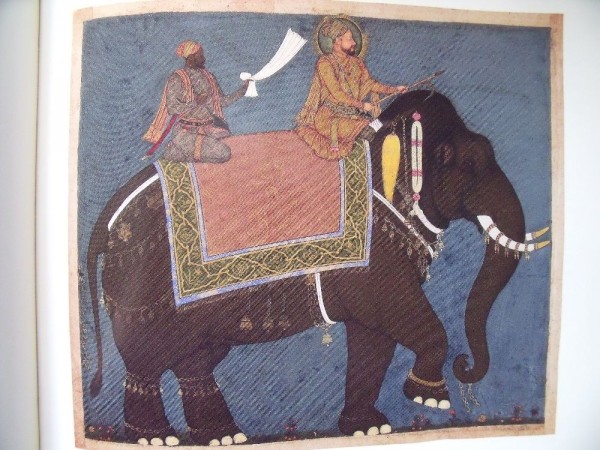

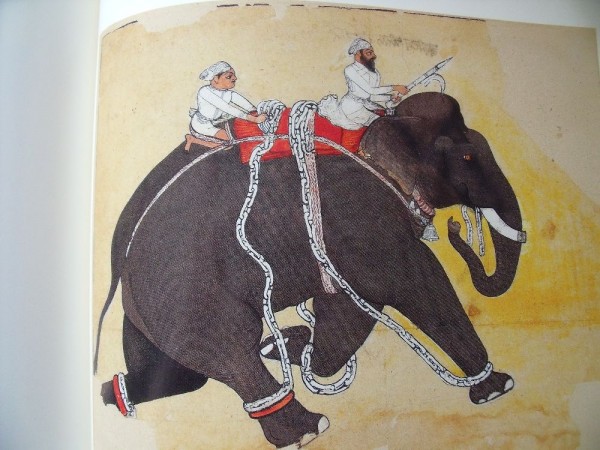

Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah and Ikhlas Khan riding an elephant

Bijapur, Deccan, c. 1645. By Haidar Ali & Ibrahim Khan

Gouache with gold on paper, 32 x 44.5 cm

Howard Hodgkin Collection

A Bijapur artist shows he has absorbed Mughal style but maintains Deccani sensibility and use of colour. While the body of the elephant is modelled quite flatly, the two men are modelled more realistically and with greater detail in both face and clothing.

Elephant at a gallop

Kota, Rajasthan, c. 1710-20

Gouache on paper, 35.6 x 1.9 cm

Howard Hodgkin Collection

Urged on by the touch of the anklus, this elephant advances at a galop in spite of the prolific chains gathered up on to his back.

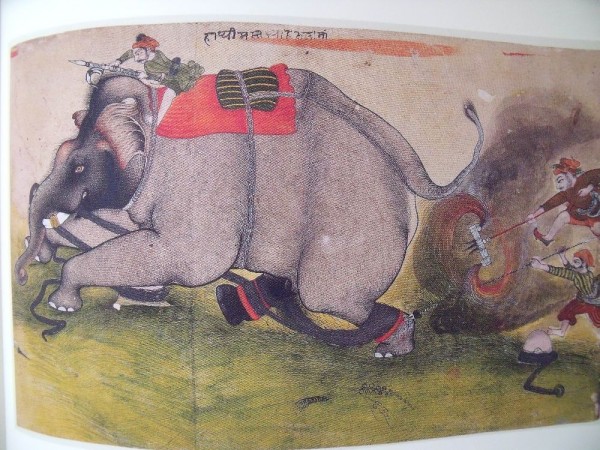

Enraged elephant

Kota, Rajasthan

Brush drawing with gouache and silver on paper

Howard Hodgkin Collection

Bull elephants can often become frenzied and aggressive during their mast season. Flaming eyes and a discharge from glands in the elephant’s temples are accompanied by unpredictability and violence. On the right,a keeper pursues the elephant, his charkhi equipped with lit catherine wheels; a second keeper wields a spear and the mahout is prodding the elephant’s forehead with his anklus.

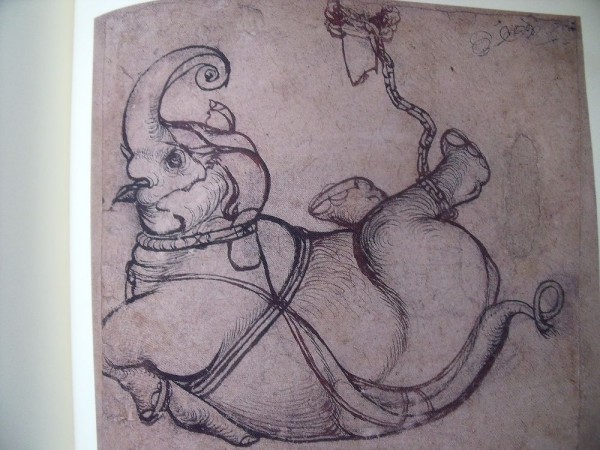

Fallen elephant

Kota, Rajasthan, c. 1700

Brush drawing on plain paper, 22 x 25 cm

Howard Hodgkin Collection

This lively, playful sketch conveys the real or imagined flexibility of a massive animal, in contrast to the more formal and earlier portrait paintings shown above.

In the introduction to the catalogue, Howard Hodgkin makes it clear that, “The pictures are chosen according to my idea of aesthetic quality, rather than any other criteria. My collection has nothing to do with art history , it is entirely to do with the arbitrary inclinations of one person.” Andrew Topsfield, who chose paintings from the collection for the exhibition, similarly states, “These pictures have been chosen because I thought they were beautiful, because they touched my emotions, and not for any scholarly purposes. It is a collection made by an artist.” The exhibition is now over, but the catalogue remains to give a taste of the life and colour of the collected images which are on long term loan to the Ashmolean Museum. (Selected images are on display in the Indian galleries.) Meanwhile, Hodgkin continues to collect, ” despite occasional resolutions to the contrary”.