Duncan Grant died in 1978 and the Charleston Trust was set up in 1980 in order to try to save his former home which he shared for many years with Vanessa Bell as well as other permanent and semi-permanent guests. From the outside Charleston appears a typical Sussex farmhouse of melting warmth and charm. Within, the charm is multiplied ten fold, which is a considerable achievement for today its domestic spaces are usually overrun within jostling and chattering admirers who’ve come to admire the decor and furnishings.

I think my fascination with Charleston came from a television documentary in the 1980s. (A recording was on sale at Charleston for may years, but I can find no mention of it now.) The dry rot, wet rot, damp, etc., could be seen to be causing devastation. Hand stencilled walls had become patchy, the textiles limp and stained and painted furniture looked dirty and rather tatty. Restoration went ahead and the farmhouse opened to visitors in 1986. It took me a few years of longing from afar before I made my first visit but after that a friend and I used to go almost yearly in June to celebrate our mutual birthdays – then the house, garden and countryside was/is at its loveliest. It quickly became the wonderful sort of place to which we took foreign visitors – somewhere you could trust to speak for itself of the beauty of England while you sat back glowing quietly in reflected glory, very good cake and tea to hand.

One time we had a wonderful guide, all twin set and pearls, neatly coiffed grey hair, polished vowels and a wicked way with words, who livened things up a bit by saying that there had been a great deal of feeding and frolicking, fiddling and faddling going on – and an awful lot of other things too that also began with f. We laugh about it now but the Bloomburyites were not as free living and loving as we sometimes assume from our C21st vantage point.

For many years poor Angelica believed herself to be the child of Vanessa and her husband Clive until, aged 17, Vanessa took her on one side, in the drawing room at Charleston nd told her that Duncan was her father. Afterwards, alone, Angelica felt exulted, describes gloating about it to herself but succinctly states that she never spoke of it to Duncan. She felt not that she had two fathers but none. The emotional inertia she suffered was to have a long lasting effect. Through wise eyes she tried to understand both men, for whom she had much sympathy, and Vanessa, whom she came to resent. These complexities Angelica chronicled in her agonisingly named biography ‘Deceived with Kindness’. Exquisitely written, full of wisdom and perception it is one of those books for the boudoir shelf overwhelming in honesty and poignancy – if not an antidote to Bloomsbury, it is at the least a reminder that Charleston was no earthly paradise. (Angelica died this year, 4 May 2012, aged 93.)

Vanessa Bell, her two sons, Duncan Grant and David Garnett had moved to Charleston in 1916 so that Grant and David Garnett, who were both concientious objectors (and lovers at the time), could work on the land They had little money to spare and did as much work on the house that they could themselves. David Garnett describes Vanessa and Duncan scouring Lewes for furniture which, “with rare exceptions were astounding objects, bargains which attracted Duncan or Vanessa because of their strange shapes or low prices… Both Duncan and Vanessa appeared to believe that the inherent horror of any badly damaged and constructed piece of furniture could be banished for ever by decoration. The strange blend of hideous objects of furniture, painted with delightful works of art, gives to the rooms at Charleston a character which is unique and astonishing..”

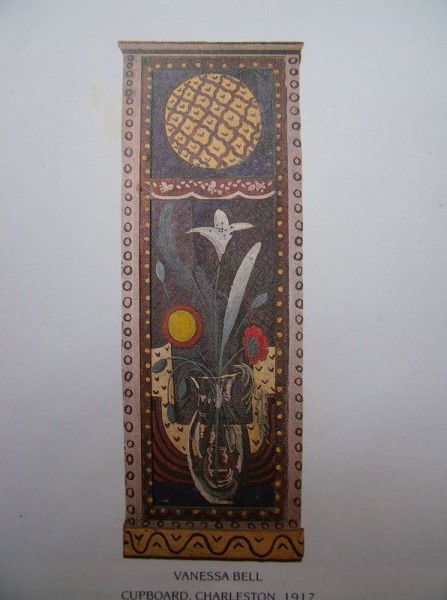

Vanessa Bell: Charleston cupboard 1917

Picture taken from Gillian Naylor’s ‘Bloomsbury’ 1990 Octopus (pub.)

Both Vanessa and Duncan had been greatly influenced by Roger Fry who had introduced English artists to what had been happening in France. Fry’s theories shocked many in the art world, especially when he found much in common between the newly fashionable frescoes of the Italian Renaissance and the much reviled paintings of the Post-Impressionists. Fry believed in being bold with his ideas. In 1910 he mounted the exhibition, ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ with paintings by Van Gogh, Gaugin, Vlaminck, Derain, Rouault, Picasso and Cézanne and it created a real stir. This was soon followed by the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912. The painters he championed were, he believed, rebelling against the photographic vision of the C19th as seen in the exact meticulous art of the Pre-Raphaelites (and their medieval-loving successors) and what Fry described as “the exact and literal imitation of nature” which inspired the Impressionists. For Fry the formal values of a painting were more important than subject matter or ‘truth to nature’. In the extreme this led to complete abstraction. However, Fry, Bell and Grant only ever toyed with and never wholly embraced this extreme. Form and colour became primary once more.

For Vanessa, the exhilaration of the exhibition was simple – now she felt free to paint as she wanted to, with attention to form and colour and with no concern for telling a story or showing things as they really were. Duncan Grant experimented more and his work had anyway been moving towards a simplification of form and content. He continued in this vein and is often criticised for being too changeable and having no signature style. I suppose that they had just enough money to paint to please themselves and their friends and hadn’t got the sort of personalities to promote their work to the world at large. There seems no indication that they took their painted furniture especially seriously, but you have to wonder whether they realised that it would be in their decorating rather than in their easel work that fame would lie.

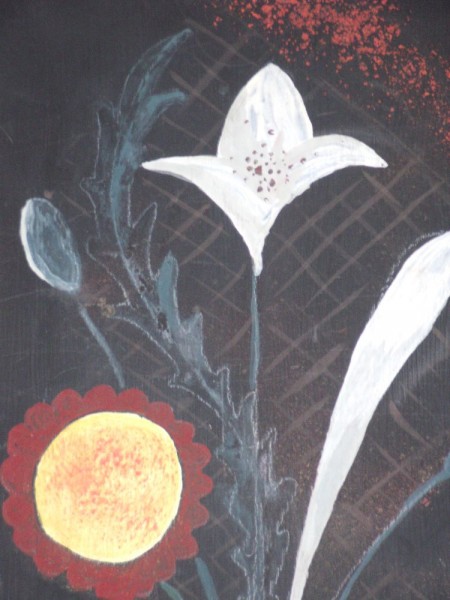

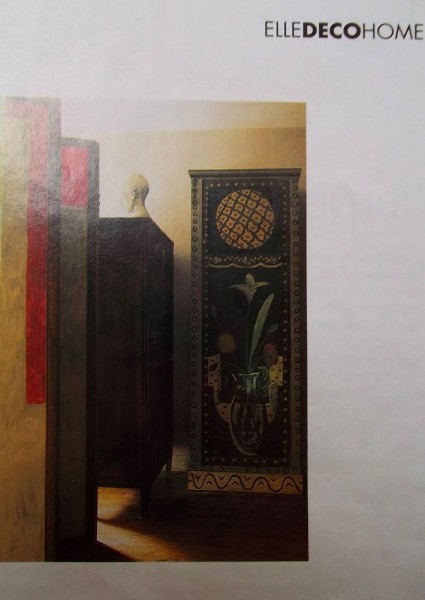

The cupboard is to be found in Vanessa’s bedroom near her bath. (Strangely, it is not photographed in most of the books about Bloomsbury.) The painting is a wonderful mix of geometric shapes and sinuous lines; colours are both uncompromising yet harmonious. My version was great fun to do and I leaned a lot by trying to copy Vanessa’s. I decided that ‘less is more’ and opted out of a more detailed background. I used matt spray paints for the background and matt stencil paints for the painted panel and decoration. Gold spots were done in Humbrol enamels. One day I shall paint the other side which I left unpainted as it was up against a bed.