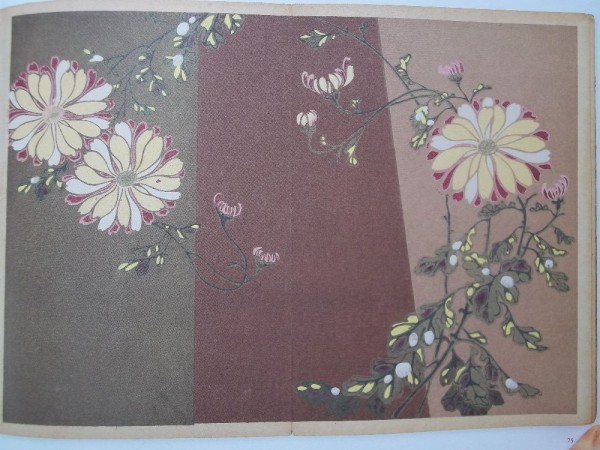

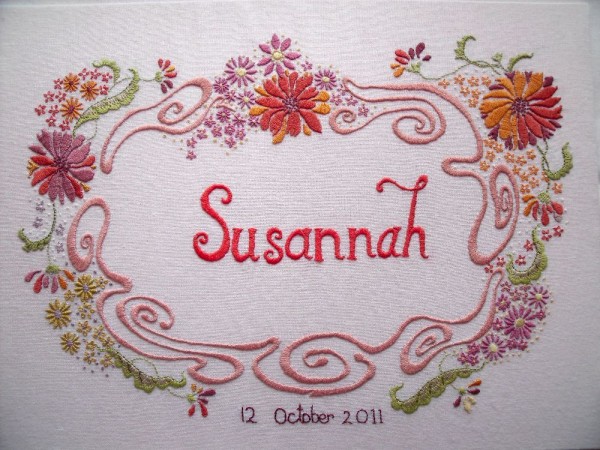

When I design an embroidery to celebrate the birth of a baby, I like to find flowers and foliage appropriate to the time of year of their birth. For some reason I have became fixated with briars, blackberries and rose hips but the symbolism of all those thorns really isn’t a good idea for the start of a new life. Fortunately, I was re-reading The Tale of Genji and I was reminded that in Japanese art and literature, just as plum blossom is synonymous with spring, so chrysanthemum is to autumn. The Japanese print below gave me the shape of the flowers and a fluidity of line that I wanted to emulate. The art nouveau squiggles were then irresistible as I love sewing curving lines of satin stitch which seem to be my default design mode.

Korin (Japanese artist, 1866-1942): woodblock print (1905)

From Le Japon Artistique’ Japanese Floral Pattern Design in the Art Nouveau Era From the Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Chronicle Books, 2010.)

Today in England, chyrsanthemums tend not to be the first choice of flower to buy. Daughter No 2 said she associated them with funerals which I think has come about because they are so hardy and long lasting. They are certainly often to be seen making a brave face of being decorative in many a village church and churchyard for that very reason. So it is uplifting to see how high they are held in the esteem of Japanese culture and especially in the literature of the Heian period, AD 950-1050, which is one of the most fascinating cultural periods in the history of the world.

At a time when Western Europe was unstable, largely undocumented and which until recently was referred to as the Dark Ages, Japan was enjoying the apogee of a highly sophisticated culture. In formal terms the predominant influence was that of China. The affairs of state and official cultural life were conducted in Sino-Chinese, a bastard Chinese, although by this time there was no longer very much interchange between the two countries and Japan was often described as having turned in upon itself. At this time, there is a more than a whiff of decadence about the Japanese aristocratic elite, especially the men with their poetry competitions, flower dances (accompanied by drinking till dawn celebrations) and ceremonial outings. Meanwhile the women lived unseen in semi-darkness in curtained recesses behind shuttered screens in rooms separated off at the ends of walkways and here they passed many inactive and probably very boring hours. However, in this foetid environment, something wonderful and unique happened for, quite extraordinarily out of these confines a new literature burst forth. The Japanese had no writing system of their own prior to contact with China. By the mid 9th century a syllabary had emerged from Chinese characters and it was this that the women writers developed for their own entertainment. (Murasaki was unusual for a woman in that she knew the Chinese used by the men.) Writings produced by women was often known somewhat scathingly as ‘women’s writing’. Yet the two most important writers of the time were women, and even more surprising were contemporary courtiers and rivals (being ladies to 2 different empresses whose fortunes waxed and waned in inverse proportion one to the other).

Murasaki Shikibu produced what is perhaps the world’s first psychological novel , ‘The Tale of Genji’ (a long book, started in the early years of the century and finished 1021) while Sei Shonagon wrote ‘The Pillow Book’ (finished 1010) a vivid, lively journal of court life full of gossip, waspish comment and analysis born of a sharp eye for detail. In both works the writer interacts with the reader to express opinions, amusement or irritation and generally makes themselves felt as fully as any character in their writing – and all of this 750 years before the world encountered Tristram Shandy or Tom Jones.

I have read ‘Genji’ twice now and find I’m drawn into the culture of this strange world. Genji himself is a charismatic figure, immensely good looking and privileged, although not quite top drawer. It is easy to find him wanting in character to begin with, for in his youth he is promiscuous and casual in his dealings with innocent, not very well connected women who eke out their lives poorly protected in insalubrious parts of the city, encased in insubstantial dwellings and bundled in swathes of fabric (curtains, up to 10 layers of clothing – it is very cold – and hair reaching to their extended hems). Ripe and ready for him their presences are revealed by quirks of fate which Genji finds impossible not to act upon. But Genji develops a conscience and he never forgets a lady with whom he has had an encounter. Even those who turn out to not be quite so good looking as his aesthetic demands are taken in, housed in luxury and given a degree of respect they may not otherwise have had. The influence of Buddhism is strong and in maturity the transitory nature of things is never far from his thoughts. He is so well-drawn a character that I feel the novel never quite recovers from his death about two-thirds of the way through the book. Bereft, you read on but never find another with whom to engage in the same way.

Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book is a quirky mixture of lists (of things she loves, things she hates, things that are good/bad/beautiful, etc.,) interspersed with factual detail about daily life in the court and capital. Around her dramatic political changes disrupt her life, but she is determinedly upbeat; she has decided she will enjoy the experience of living whatever happens. As you might expect in a closed society, clothes become a source for much enjoyment, examination and comment. Delight comes in glimspes of young men wearing splendid uniforms – chamberlains of the 5th rank are particular favourites. Similarly much thought goes into the organisation of the layers of sleeve that are the only bit of a woman’s dress which may be shown in public – mille feuilles of fine fabrics just visible peaking out from under the slatted carriage sides or sneaking out from the bottom of verandah blinds. In semi-darkness sound and scent are everything. When she mentions the soft tap of a lid placed on a kettle or the memory of the lingering scent of incense from a courtier’s heavily-scented gown, she stirs the reader’s memory just as sharply as her own was touched.

From these books we can discover how deep are the roots of the Japanese love of chrysanthemums. Fittingly for my embroidery, the flower was deemed an auspicious presence at a birth promoting a long and sturdy life. Both Murasaki and Sei Shonagon describe the tradition of the Chrysanthemum Festival. Chrysanthemum blooms in the garden are covered with cloths (some say they should be cloths of chrysanthemum patterned brocade). On the next day, when the dew of the festival morning has soaked the cloths and the perfume of the flower is heavy in the fabric, the cloth should be used to wipe over the face and body in order to prevent ageing and an early death. During the banquet, at the same festival, again to encourage longevity, wine in which chrysanthemum flowers had been steeped was drunk. Palace dancers brought small white trout to the Emperor and these were then cooked and served to his guests. Frost withered chrysanthemums were particularly prized.

The origin of the Chrysanthemum Festival was Chinese. It was also known as the double nines as it was celebrated on the 9th day of the 9th month. Nine was a very powerful number, being the highest odd number before 10. The double nine is accordingly doubly auspicious and came to have associations with virtue and virtuous behaviour. Interestingly when Japanese bow repeatedly, this is known as the nine bows as the Japanese for 9 also means to bow repeatedly. In modern Shinto wedding ceremonies 9 offerings (3 x 3) nuptual cups of rice wine continued the symbolism.

The Chrysanthemum Festival meant careful nurturing of the flowers so that they should be quite ready for the special day (shades of the Chelsea Flower Festival). They were particularly loved as they were seen to be at their most splendid when most other flowers were fading and dying away. Eventually, this festival merged with a general celebration of the harvest which was celebrated in the 9th month on the 9th, 19th or 29th day and later, when the solar calendar was adopted rather than the lunar, there was the difference of a month and the blooming of the flowers no longer coincided conveniently with the harvest. Nevertheless, today the Japanese royal family still celebrate the chrysanthemum on the 9th day of the 9th month and this is appropriate as their seat of power is known as the Chrysanthemum Throne.

The michaelmas daisy is named for its flowering around the feast of St Michael, the 29th September. A harbinger of autumn, it is much appreciated by bees and butterflies seeking the last vestiges of the summer’s beneficence. Both plants belong to the botanical family, Asteraceae; the michaelmas daisy is of the genus Aster, the chrysanthemum of the genus Chrysanthemum.

Bibliography:

Murasaki Shikibu: The Tale of Genji (Translated by Edward Seidensticker, Secker & Warburg, 1976. This is the one I have. Arthur Walley’s translation of 1921-23 is very much enjoyed for his lyricism, though he is often thought to be too free. Royall Tyler’s translation dates from 2001 but I haven’t read it).

Sei Shonagon: The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon (Translated by Ivan Morris, OUP, 1967; also translated by Meredith McKinney, Penguin, 1997. I have had both. Arthur Waley also translated it in 1928 and the same comment as above applies)

Ivan Morris: The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan, OUP 1964. Fascinating. Wonderfully informative.

Le Japon Artistique: Japanese Floral Pattern Design in the Art Nouveau Era: Chronicle Books, 2010

Laurence Sterne: The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1759-1767)

Henry Fielding: The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749)

One Comment

If some one wants to be updated with hottest

technologies then he must be go to see this website and be up to date daily.

2 Trackbacks

[…] bit limited at the end of October unless it’s chrysanthemums and michaelmas daisies (done here) but then I realised how berries and seed heads were also rather lovely and often more interesting […]

[…] has its own long history, having developed in an unbroken tradition over at least 1,000 years. Read The Tale of Gengi for brilliant descriptions of kimonos which differ little from the garments we know today, except […]