I use a lot of linen for making wedding and christening cushions and as backing for embroidered hangings, so I have found it sad that you don’t often find British linen made from indigenous flax. This summer I have started to notice the above plant growing in clumps along the side of not just the main roads but also along roads in the village. Several times, I have picked some and returning home, I’ve photographed it as quickly as I could but the flowers wilted and turned even more raggedy very quickly. Consulting flower books and internet images, it becomes apparent that flax can vary considerably as to the shade of blue and as to the shape of the petals but one thing that the entries do agree upon is that the flower should have 5 petals. And that’s where I have problems as the flower is so ragged it is hard to tell, even if you try to pull the individual petals away from the calyx (?I think) with a pair of tweezers.

Unfortunately, my well-informed farmer/church warden says he’s not very up on wild flowers, but my point is it may not be a wild flower but a cultivated flower. I think he was particularly disparaging as the soil round here isn’t really ideal for flax growing which prefers more fertile, nutrient rich earth. Well, I was just beginning to think the fantasist in me was taking over and that my wish that I should be surrounded by nascent fields of emerging blue flax was becoming mother to the thought. Then last week, we were enjoying the vicarious privations of life on ‘Wartime Farm’ on BBC2 when we learned that during the Second World War many farmers were encouraged to grow flax by the Ministry of Agriculture in order to provide things like webbing for parachutes. And, when you think about it webbing is just the sort of word that in itself conjures up all sorts of war time images – uniform belts, rucksacks, harnesses, gun holsters, straps of every kind, sturdy camouflage nets, seats where rushes and reeds aren’t available, blanco covered gaiters, hat bands and of course, ropes. Most of these things very rarely raise their heads above the war time horizon and I think it is only on the vary rare occasion that I have so much as uttered the word ‘webbing’, let alone given it much serious thought. So, my latest ruminations make me wonder whether flax was grown during the war on some of the lower lying, more fertile land nearer the Thames. Although the fields would have returned to the more usual crops after the war there may have remained pockets of flax at the edges of fields and at the bottom of hedges. The odd bit of flax could have flourished and its seed could well have been dispersed by the wheels of passing traffic and found road verges an ideal site for germination. I would love to find out if there is any truth to my speculations. Meanwhile, in summer, I shall continue to enjoy the splashes of intense blue which brighten my bus journey to and from work.

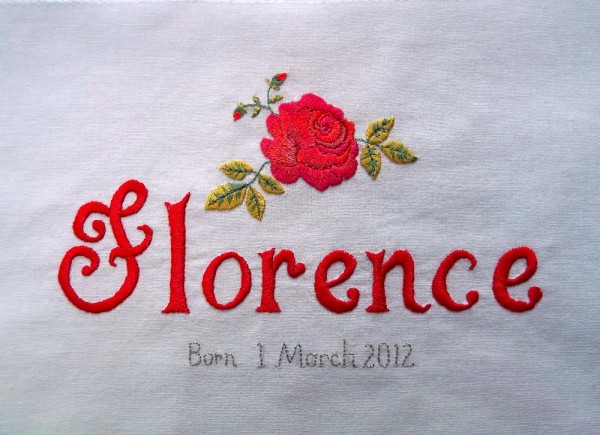

This is my latest piece of embroidery on linen, made as a present for a little girl baptised in the village church by my husband 3 weeks ago (I’m always late with these things). The church was full of family, friends and villagers and the weather was uncharacteristically on the side of a baby dressed in her finest christening best who was about to have water poured all over her head several times. Excellent baby made not a peep but smiled throughout. The instant coffee was rather a let down considering the slabs of the most chocolatey of brownies and cookies the size of small frisbies (made by the family) but our usual 2 giant cafetières would have baulked at serving more than 50 people. Celebrations and more good food then continued back at the parents’ house and we all made a note of the splendid marquee, a thing of beauty with its wooden supports and white spider’s web of guy ropes, the envied possession of a guest from a neighbouring village. (We have had so many weddings and christenings in the village recently, that most of us have become marquée connoisseurs and can talk for several minutes, although reaching no discernible conclusion, on the relative merits of the metal-framed version to the pile-driven wooden poled variety.)

Interestingly, an early version of the Sleeping Beauty story, ‘Sun, Moon and Talia’ by Giambattista Basili, which was reworked into the story we know today by Perrault, involves the newly born child having her horoscope read and the prediction made that she will have her life endangered by a sharpe sliver of flax. Flax is banned from the land but, as with the more familiar telling, the adolescent girl comes upon a forgotten spinner, pricks her finger and falls into a deep sleep. She is placed in her father’s country house where she is discovered by the king who is so moved by her beauty that he sleeps with her and causes her to conceive twins – Sun and Moon. This version of the story gets much darker at this point for the king leaves her and she gives birth, alone and still unconscious, to her two children. The boy child, seeking to suckle from her breast, sucks her finger instead, removes the sliver of flax and causes her to wake up. The king returns briefly to Talia but is unable to break with his life in the palace with his queen. During broken nights, nightmares reveal his secret to the queen and she, with a great deal of Snow White’s stepmother about her, plots Talia’s and the twins’ demise. Talia is saved, lambs replace babies in the palace stewpot and the wicked queen gets her due punishment. The cook tells the king how she has saved Moon and Sun. Talia becomes the new queen and Sun and Moon live on.

2 Comments

But why is flax considered so dangerous by both renditions of the Fairy Tales that it’s apparatus pricks someone so disastrously when it is clearly also so productive? Written on my iPhone from top deck of 43 bus, in Friday night rain.

I have no idea, but will try to find out more.

One Trackback

[…] Four years ago I blogged about flax plants which I felt sure were springing up in profusion along not only country lanes but even the main roads. I waxed lyrical about how it was possible that they were the repetitively self seeded remnants of flax ancestors planted during WW2 for use in webbing for parachutes and other similar necessities. In fact, I found myself so seduced by the romance of this notion that I mentally flicked away any doubts that ambushed me from time to time. Well, having embroidered these little blue flowers for the altar frontal, I must now come clean, for these plants are not flax but chicory. It is true that the two plants are very similar but the very thing that made me hesitate to call them flax – their ragged petals – was the thing that finally convinced me they were chicory. (For photos of chicory and a brief fantasy on flax, see this post from 2012). […]