Just before Christmas, daughter No 2, our one woman caravan, returned for a holiday from her work in the Far East and, once again, she overindulged the family with the most wonderful of gifts – some things useful in themselves (pottery, toilet bags, wallets, etc), others gorgeous in themselves (fabrics in bright orange, yellow, turquoise and midnight blue that bring the itch to eager quilting fingers) and things purely decorative in a frivolous and transitory way, like fabric baubles and doves for the Christmas tree. (Await a future post for pictures of these.) This year she also brought home some traditional skirts, which she had bought for herself – obviously old, I suppose we would call them vintage.

Vietnamese skirt (vintage) worn by daughter No 2: indigo hand dyed with cross stitch embroidery and batik

As country director for MAG (Mines Advisory Group) Vietnam, a non-profit-making NGO, daughter No 2 travels the country overseeing not only landmine clearance by highly skilled professional international staff but also visiting the many community projects which train village people so that they can take up paid work tackling some of the local clearance for themselves. This work takes her far off well beaten tourist tracks and enables her to see at first hand a Vietnam very different from the increasingly westernised life of the city dweller.

Vietnamese skirt showing detail of batik and embroidered and appliquéd panels (skirt restyled and rescued from original garment)

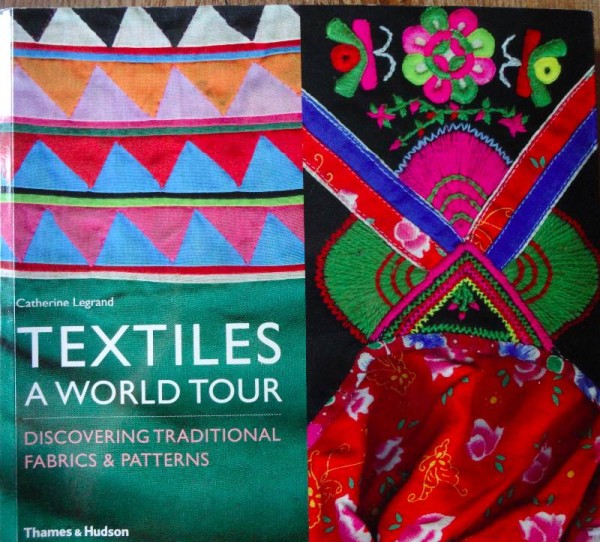

For nearly 30 years of the C20th Vietnam was at war. In the 1940s the fighting began between the colonial French power and the communists. War finally ended with the communists seizing the southern capital, Saigon and taking over the whole country in 1975. The bit most people remember is the American intervention of 1965-73. During these years Vietnam was essentially closed to the west and we got to know very little about the culture and customs of Vietnamese tribes. Perhaps it isn’t too flippant to suggest that one of the first inklings we had of the country’s craft traditions came when the Japanese fashion designer Kenzo sent his colourful pleated wraparound skirts inspired by traditional Vietnamese skirts down Parisian catwalks in the late 70s. Catherine Legrand in her brilliant 2008 book Textiles: A World Tour (Thames and Hudson) has researched the fascinating styles of dress of the region and through explanatory sketches and good clear colour photographs she reveals a rich textile culture of surprising complexity that makes for absolutely riveting reading. (Catherine Legrand has recently written Indigo: The Colour that Changed the World, T & H 2013.)

Vietnamese skirt showing batik and embroidered panels. (old and probably originally part of a much bigger and longer traditional garment).

The mountainous region extending across North Vietnam, northern parts of both Laos and Thailand and bordered by China further north and by Myanmar (Burma) in the west has become home to many ethnic peoples. Originally from China these peoples have somehow maintained their own customs, beliefs and language as well as highly distinctive styles of dress – in fact so distinctive are the latter that the names by which the various communities are identified derive from details of the most distinctive features of their costume. In this way, tribal groups are variously called the Red Yao, the Flowered Hmong, Black Hmong, White Hmong and the White trouser Yao. (The Yao are spread across national frontiers; there are the Vietnamese Yao, the Laotian Yao and the Chinese Yao.) Below are summaries of some of the main tribal groupings and their style of dress.

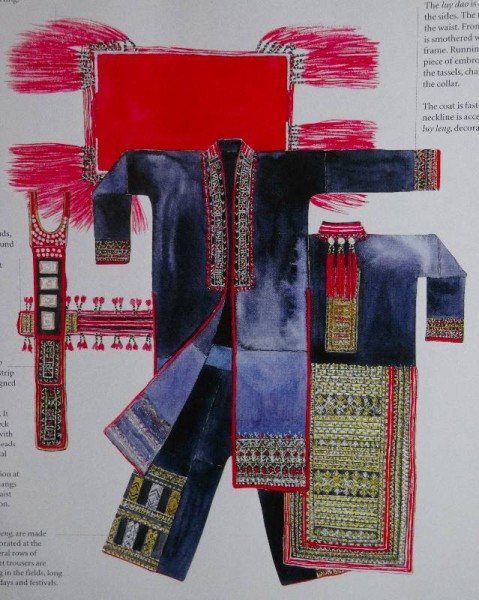

Red Yao women wear distinctive red headdresses decorated with many red tassels. Hair is twisted up in a chignon and tucked beneath the first red scarf; 3-4 further red scarves (up to 10, symbolising the wealthy) may be added and the eyebrows and forehead are plucked to reveal a smooth expanse of skin. The coat is straight with panels of embroidery in specified places and distinctive for the line of long red tassels which fall from the base of the back of the embroidered collar. Belts and bags may have more tassels. Trousers not skirts are worn and these have embroidered panels towards the bottom on the outside of the leg.

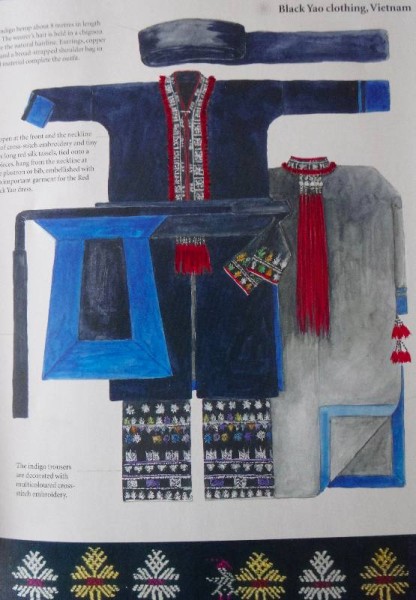

The Black Yao are found to the west of the Red Yao and here the headgear takes the form of an enormous indigo turban formed from one long piece of fabric. Coat and trousers are similar to those of the Red Yao although there seems to be less embroidery. Along the front opening of the coat a narrow band of cross stitch embroidery is often outlined with tiny red pom poms and the red tassels falling from the back of the neckband extend to below the waist. A plain blue apron is usually worn at the front, low on the waist.

Women from the White Trouser Yao tribe (not to be confused with the Tight Trouser Yao) are, confusingly, usually seen in indigo trousers as the white trousers are reserved for ceremonial occasions. However, they are still quite easy to distinguish as they wear a plastron (a sort of apron worn over the chest on a silver torque) of unbleached hemp which is heavily decorated with brightly coloured cross stitch. The star is a popular motif and black painted teeth, once the height of WhiteTrouser Yao fashion, can still sometimes be seen.

White Trouser Yao clothing, Vietnam (from Catherine Legrand’s book Textiles: A World Tour, T & H 2008)

The Flowered Hmong love the complex pleated skirt that so inspired Kenzo for his haute couture designs. Structurally it is made of 3 horizontal bands. A plain indigo linen/flax band is heavily pleated at the waist and to this is attached a deeper band of batik (blue/white) with criss-crossed red braid and an appliqué of squares (on end like a diamond) within squares. This band traditionally had double the pleats of the top one. Finally there is a band of squares – cross stitch embroidered designs alternating with appliquéd squares in both plain and floral cottons. Hmong women from some regions buy imported skirts of synthetic fabric, while others take great pride in doing all the embroidery and pleating by hand. In China, just over the border, the skirts of the Miao women are batik all over or beaten, a process called calendering, which gives the fabric a purple sheen.

Vietnamese skirt of the Flowered Hmong (photographed from Catherine Legrand’s book Textiles: A World Tour T & H 2008)

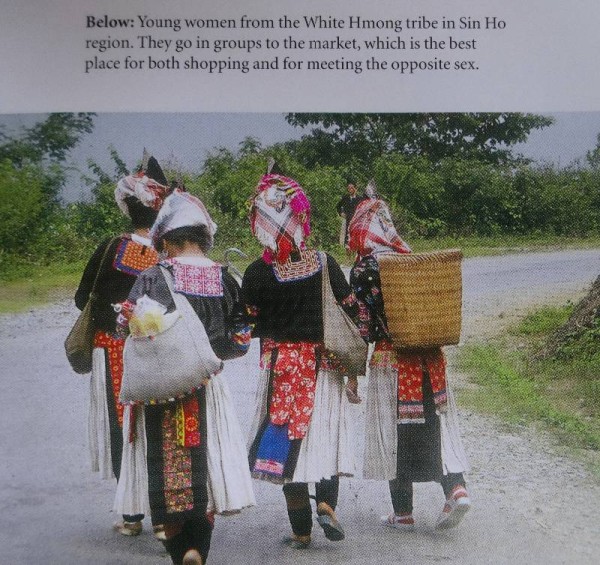

White Hmong women wear full gathered skirts of unbleached fabric (either cotton or ramie which is produced from a plant of the nettle family). Two long brightly coloured embroidered aprons hang at the front and the back to help keep the skirt clean. Sadly, today this skirt is often replaced by a pair of black trousers. The White Hmong are especially skilled in the technique of reverse appliqué which is used on collar and cuffs.

Vietnamese White Hmong Skirt girls (photograph from Catherine Legrand’s Textiles: A World Tour T & H 2008)

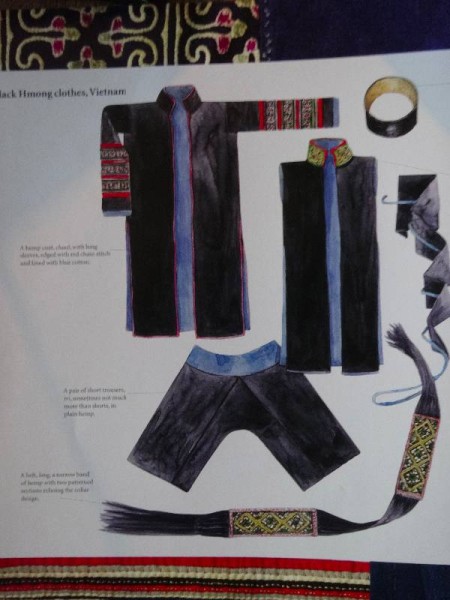

Indigo is the hallmark of the Black Hmong who dye their fabric several times to ensure a blue so deep it appears black and the women themselves look as if they have been soaked head to toe in a vat of indigo dye – particularly as their hands are blue from handling the dye and their calves are stained blue from tight fitting ankle to knee indigo-dyed leggings. Silver jewellery, red fine binding and the option of embroidered collar and cuff bands add flashes of detail. Formerly the costume included blue/white batik skirts but few of these remain outside museums or the family chest.

This list is by no means exhaustive, though I have found it exhausting trying to be clear in all the details. I have completely lost all reference to the place where I saw anything other than mere mention of the Tight Trousered Yao and I have left out the seed embroiderered clothes of the Xa Pho, the harlequin costumes of the Lolo, the Bo Y blue and white batik skirts, the Pupeo skirt with its brightly coloured appliquéd hem and the bright strip patchworked sleeves of the Hani and Lanu women.

I am particularly sad at leaving out the appliqué sleeves of the Hani and Lahu women as I feel it would be a rather good look to eumulate.

It seems to me that the skirts that my daughter has come home with are all that remains of fine pieces of once glorious workmanship, neighbouring bands having been recycled or perished. I began this post hoping to identify what style of skirt they were but I end it no wiser as to specifics though in general terms considerably more informed.

Detail of modern Vietnamese purse showing cross stitch panel. Here the dyes look to be synthetic rather than natural,

I would love daughter No 2 to take lots of photos and purchase more old textiles when she returns to Vietnam. However, in researching this post, I have dipped into various blogs of travellers who have gone to Vietnam on a mission to seek out textiles and I am disappointed to discover how many of these have been intrusive and insensitive in their research. Many villagers are no longer willing to be photographed in their finery as they sit in groups sewing and they are often equally unwilling to sell the results of their handiwork. It’s impossible to tell how common this sort of behaviour is amongst people who travel to these more inaccessible sort of places but a bit of me thinks that perhaps we should leave these gentle people alone.

2 Comments

I really enjoyed reading this as I am doing a presentation of my travels in Vietnam and trying to sort out the embroidery and photos I have si I know it’s accurate . I did keep a sketch book which helps .

Have you seen any more Vietnamese textiles since ?

Thank you for your blog

Helen

Thank you Helen. The Catherine Legrand book mentioned at the end of the post (and from which come all the sketches on the blog) is excellent and should help you sort your Vietnamese textiles out should you want a really comprehensive authority.

My daughter is now working in Cambodia so she still picks up textiles from that corner of S.E.Asia. Sadly, Mekong Quilts which had shops in both Vietnam and Cambodia have just had to close as a direct result of the pandemic. It’s a great shame as they provided an income (hand sewing and quilting) for many women living in the delta area where farming and similar activities are very precarious. We hope they may be able to start up again at some point.

5 Trackbacks

[…] mentioned reverse appliqué decoration in my posts on Vietnamese skirts and afterwards I remembered that when daughter No 2 spent her gap year inVietnam 15 years ago she […]

[…] attracted lots of spam comments, very few of which seem to have anything to do with Vietnam. (See here for Vietnamese skirts and land mine clearance, here for Vietnamese ceramics and […]

[…] textiles which I wanted to learn more about. At Christmas she came back with a fantastic traditional skirt (here are a couple of skirts made from rescued textiles but if you scroll down there is a picture […]

[…] more about just some of the ethnic tribes see an earlier post of mine here or even better pick up a copy of Catherine Legrand’s ‘Textiles, A World Tour’, T […]

[…] and brief descriptions of the traditional embroidered clothes of the main Vietnamese tribes see here. Daughter No 2’s skirt above is very like the splendid skirt of the Flower Mong shown in this […]