Sadly, Cheltenham’ s collection of costume has received little airing in recent years. Shortage of exhibition and storage space means its shrouded garments hang anonymously along the length of the corridor that used to be known as Gallery 13 (a useful exhibition space in itself) in an area that is now closed to the public. Since her appointment in 2010, the Wilson’s conservator (part time) keeps her eye on the collection and has even managed, along with a volunteer, to make new padded coat hangers which had become necessary – bought ones would have been well beyond her minimal budget. But otherwise there the frills and furbelows, fichus and frogging, smock coats and frock coats droop unworn and unseen, quietly and slowly deteriorating – which is distressing in its own way, unimportant as it might be in the larger scheme of things.

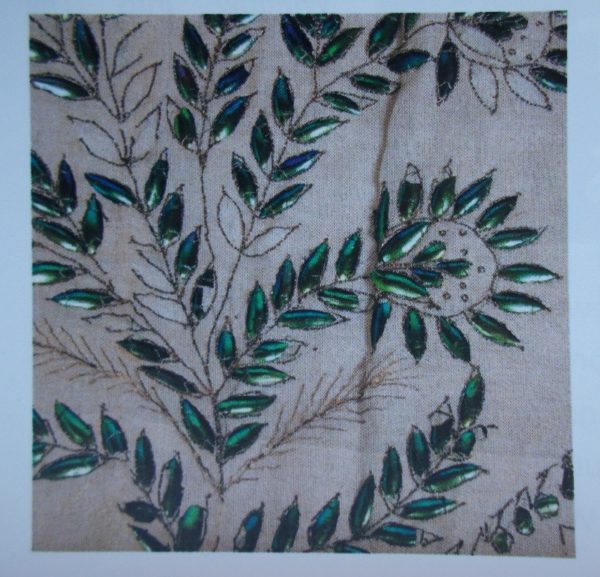

Embroidery using beetle wing cases (detail from dress in the collection of The Wilson, Cheltenham)

How things change. In the late 1970s my husband, as the then director of the Art Gallery and Museum, negotiated display of the costume collection on the upper floor of the Pittville Pump Room (built in 1830 and the largest of Cheltenham’s spa buildings) – a truly splendid location where garments and building complimented each other to mutual enhancement. The costumes had their own enthusiastic curator who came to know the collection as well as the items of her own wardrobe and her lively talks on the subject meant she regularly shared what she knew. Sadly, changes in organisation at the turn of the millennium saw the costumes withdrawn from the pump room and then latterly, with the reduction in staff numbers, the position of costume curator per se ceased to be.

On a happier note, the member of staff formerly in that role is still with the museum and on the 18th of January, Sophie Wilson (formerly costume curator, now in charge of exhibitions) and the conservator, Annik Brown told us the story behind one interesting dress from the collection which is currently on display in the gallery, a muslin dress embroidered with beetle wings made in India for a society lady whose husband worked for the East India Company and who in retirement came to live in Cheltenham.

Dress embroidered withvbeetle wing cases (dress in the collection of The Wilson, Cheltenham)

Beetle wing embroidery is an inaccuracy on my part for it is not the wings themselves which are used in embroidery but the hard wing casings, the elytra, which protect the more delicate wings at rest and which during flight lift out of the way to allow the wings proper to beat. Made of chitin (similar to keratin, the protein which makes up our nails and hair) these wing cases have brilliant metallic colouring as a result of a phenomenon known as interference, – light waves breaking up as they move through tiny spacings in the top layer of the elytra. Though the colour seems to fluctuate in shifting light, it is pure and has a brilliant intensity which some colourists say is unparalleled by any other pure pigment. The owners of these wings come from various species of wood boring insects, e.g. Sternocera aequisignata, whose adult life spans 3-4 weeks. The many natural deaths resulting from so short a life mean the wing cases were collected in large numbers from forest floors across most of southern Asia. Today the insects are also farmed as an everyday food source, and the wings, a byproduct of this, are readily available online.

Purchased wings come in their natural shape – an elongated oval with one pointed end – and once drilled can be used like that, as on the dress above Or, they can be snipped into a circle, drilled or pierced with a central hole and used like an ordinary sequin.

Embroidery using beetle wing cases (detail from dress in the collection of The Wilson, Cheltenham)

The muslin dress at The Wilson has been carefully conserved in accordance with proper techniques where the thin fabric has damage but even after careful cleaning by hand the dress is now very grey and discoloured and many wings are missing. The dress stands before us in its display cabinet reminding us of an age when women were small in stature and waists were tiny (assisted by corsets), when the fabric was hand woven and when every inch of the dress was sewn by hand. Part of me longs to ‘mend’ it rather than ‘conserve’ it and I’d love to try to wash it and make it bright again or incorporate part of it into something that could be worn now … but that’s why I’m not in the museum business, and a good thing for posterity too!

Embroidery using beetle wing cases (detail from dress in the collection of The Wilson, Cheltenham)

P.S. I did get to the May Morris Exhibition at the William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow and thought it was excellent. You could get up very close to most of the embroideries and see the individual stitches clearly. A great selection of books were available for sale (some of which I hadn’t seen anywhere else) and the standard of things for sale in the shop was high. I bought some beautiful cards with hand printed letters from a William Morris alphabet – and wished I’d bought more (framed they’d make the sort of present I’d be very happy to receive). The coffee – which I needed as it was a cold and windy day and I had visited most of the rest of Walthamstow before finding the gallery – was also excellent. The exhibition finishes tomorrow.

16 Comments

This is a fascinating post. I had no idea insect parts were/are used to decorate fabric. Thanks.

I’m glad you enjoyed hearing about the beetle wing embroidery, Ann.

As usual this post not only shows a wonderful embroidery technique but is most informative too. Thank you for all your interesting and chatty posts.

It’s lovely to hear you found the post interesting, Jill.

I also got the May Morris Exhibition, and was completely blown away by it. And by May, who seems to have been quite a character.

The beetle wing embellishment is very striking, isn’t it! But oh, yes, the frustration of knowing how little we know, even when there are extensive collections, because the time, space, and expertise are all out of financial reach..

Yes, Rachel. It’s fascinating how May’s personality and achievements are only emerging now, 80 or so years after her death.

Similarly museum collections include much whose significance is as yet unknown and unappreciated.

I loved the quotation from May that was on one of the walls:

“I am a remarkable woman – always was, although none of you seemed to think so!”

There was a lady you wouldn’t want to mess with!

Yes, I was taken with that quotation. It’s good to discover she valued herself and that we no longer have to think of her as some shrinking Victorian violet.

Those elytra make spectacular embellishments! I had no idea anyone used bettle casings in fashion. As a little kid, we had some bright green shiny Japanese beetles that fed on out ripe figs. I always thought their shiny green ( similar to what is shown here) to be lovely, even if the beetles as a whole weren’t.

In Japan beetles called Tamamushi (Chrysochroa fulgidissima) are used in a similar way. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chrysochroa_fulgidissima Perhaps these are your beetles.

I tried looking them up as June bugs — what we called them-+ adding in California to the search. Fig beetles is a more official name. They look like the ones you found above, but are more rounded in shape. It is their underside that is really glossy and spectacular.

Yes – looking up ‘fig beetles in California’ says they’re part of the scarab family and are quite different. Probably you couldn’t use their undersides for embroidery – the wing cases are easier to detach as they’re just attached at one point, but perhaps their colouration works in the same way. Interesting, Amara. We have no bugs anything like as exotic in England.

Really fascinating! My husband and I spent yesterday at the Fitzwilliam Museum’s samplers exhibition which inspired similar awe! Includes whitework…

Elizabeth

I’ve just had a look at the Fitzwilliam’s samplers online and they look splendid.

Thanks for such an interesting post Mary. Such clever upcycling!

I’d never thought of it that way, Nella, but you’re right, it would be a shame to waste the wing cases.

One Trackback

[…] could just be collected from the forest floors in South-East Asia. (See this post on a C19th dress decorated with beetles in Cheltenham’s costume collection at The Wilson.) Since I’ve been researching beetles, […]