A June birthday is the very best sort, poised half way through the year with better weather and a bit of warmth more than likely. When I was younger I knew few people with birthdays at this time and then suddenly a few years ago new friends and relatives appeared many of whom I now have to share my birthday month with. One of these is my son’s girlfriend and it is for her that I embroidered this little unicorn amid meadow flowers.

Unicorn in a meadow (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

When not embroidering I have been reading The Knot by Jane Borodale (Harper Collins, 2012) about the making of an Elizabethan flower garden. I bought the book in the shop at Lytes Cary Manor in Somerset a few years ago and, like flint in fields of chalk, it rose from the bottom of a box to the top of my notice during our latest unpacking. Set in the C16th in Lytes Cary Manor, the book is a fictionalised account of the life of the botanist, Henry Lyte who translated a foreign herbal and reordered the land around his house, with orchard, espaliered walls and knot garden. Sadly, not a trace remains of Henry’s garden as after him the land around the house all too soon returned to the farmland it had been before. More happily, 200 years later, in the early C20th, Sir Edward Jenner bought the house and started an Arts and Crafts garden, a style which echoes aspects of Elizabethan gardens. Jane Borodale, author of The Knot, likes to think that somewhere on the damp low lying land towards the River Cary grow weeds which are descendants of the plants that Henry Lyte battled with.

Detail of unicorn in meadow (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

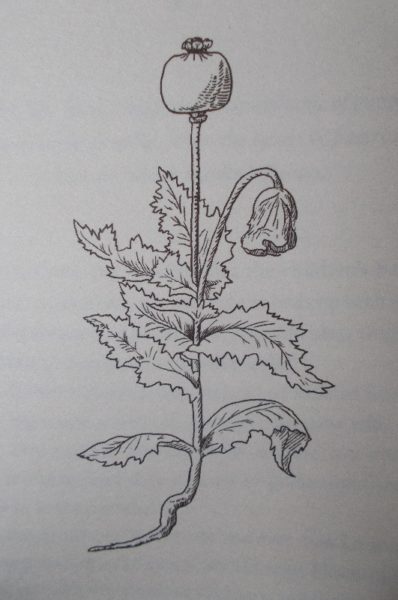

Though an observational botanist and a practical gardener (John Aubrey, commended his plant collection), Henry Lyte concentrated on translating Rembert Dodoens’ Dutch Herbal of 1564 – which he did curiously via the French translation by Charles de L’Ecluse, checking each plant as he went to pin down the right English name to match the plant’s descriptions. We know Dodoens was happy for him to do this as, before publication of Lyte’s book, he suggested more woodcuts of the plants should be commissioned to add to the original ones produced for his own book. Lyte’s book was the first extensive list of plants in English, became a standard text in the late C16th and is said to have been used by Shakespeare for his botanical references. There is a copy of Lyte’s book on display in the house.

The C16 was awash with pioneering botanists and zoologists, most of whom knew Lyte and visited him often for Somerset field trips. Until I read the book I hadn’t heard of Lyte but in researching the text for my Elizabethan jacket I had met some of the others. Thomas Penny, a good botanist though really more of an entomologist and Thomas Moffat were frequent visitors. Both travelled to the continent and sent back specimens they thought Lyte would find interesting. In the novel, Moffat somewhat mischievously brings a potted oleander as a present, though “…every part (is) poisonous to man and beast”. “There is no place for needless poisons on farming land” (Lyte). “Love it for its wicked beauty” (Moffat). Lyte loathes the plant and hopes it will perish when the season changes. (Frances, his wife, enamoured of the plant and mindful of the harsh winter climate for such a delicate plant, remembers to take it inside for winter.)

Unicorn in meadow (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

In real life, Moffat was to prove to be not just not charitable but positively duplicitous. Penny died comparatively young in 1588 and bequeathed his incomplete manuscript on insects to Moffat hoping he would finish it and publish it in their joint names. Instead Moffat rushed out a book on insects in his own name. He then prepared a new manuscript based on Penny’s work. The first few chapters were his own on bees but the remainder of the text was a rewrite of Penny’s along with 500 of Penny’s drawings. Bored, Moffat put the MS to one side, published a book on silkworms … and became an MP! In 1602 when research similar to Penny’s was about to be published in Italy, Moffat was sufficiently galvanised to pick up his quill again, only for death to intervene once more – this time, his own. Fortunately, Penny’s widow regained control of the MS which she sold to the king’s physician who published it – finally in 1634, 46 years after Penny’s death!

Jane Borodale: The Knot (Harper Collins, 2012)

As a novel, the book wooed me and won me. Casting off C21st sensibilities as to what we expect of a family man (and he did have 13 children, if I’ve counted correctly), Henry Lyte comes over as a man battling various roles and dealing with the tensions that came with them. The garden and plants are his obsessions, the management of his property is his duty, while the dispute over his father’s will is an ever present headache, throbbing along as background to all thought. Care of his family lies with his wife and servants, though individual children are taken with him to buy or look for plants. When death comes – his first wife, 5 children – it hits hard and guilt is never far away – whether it be Henry’s or the blind widow’s for her own loss, as she sits making baskets outside the hovel at his gate. Skilful and economic writing makes each death so touchingly unique. Magdalen, just two, in company with fellow botanists, including Penny, sees a squirrel up a tree and and announces, “squiggles’ – her first word. How proud Lyte was. Just days later Magdalen is dead. Little Johnny, his first son, begins to wet his breeches regularly and is frequently chastised. Kidney stones are diagnosed, suffering is intolerable and a drawn out death follows. Lyte can’t understand why his wife is not with the child but sits at the clavichord, playing interminably. Grief divides and it is only much later in the book that she tells her husband that music made Johnny less frightened. “He said he thought that each musical note my fingers struck was like a butterfly, flying up the stairs towards him, gathering in the room about him. When there were enough butterflies to bear his soul away, he said , he would be gone and it wouldn’t hurt anymore…. Play faster, mother, more notes…”

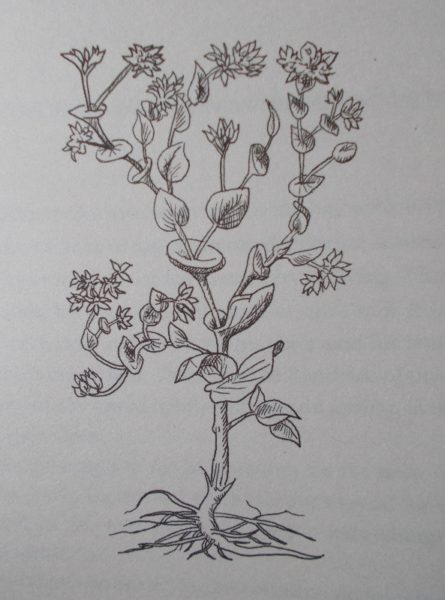

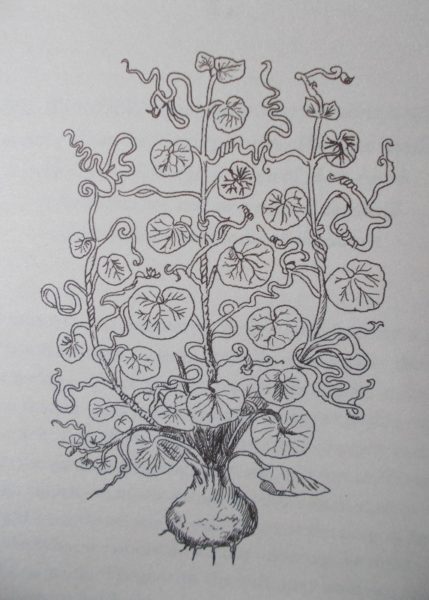

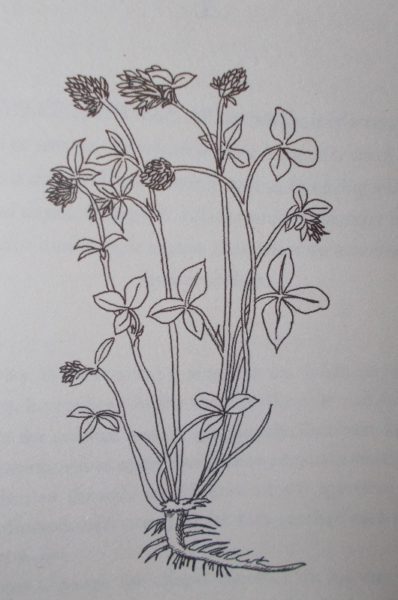

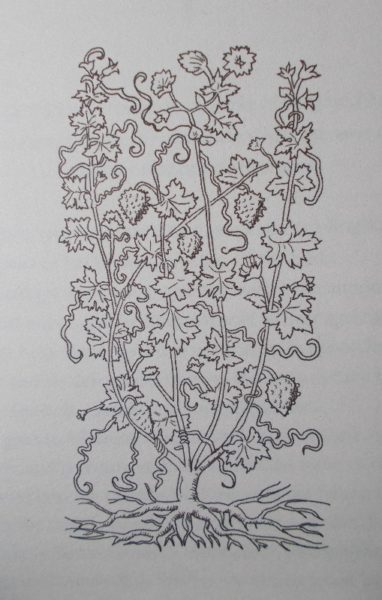

Illustration by Andrew Pinder, redrawn from the Cruÿdeboek by Rembery Dodeons (from The Knot by Jane Borodale; Harper Collins, 2012)

There are lighter moments. I especially enjoyed the drying of the washing – and goodness knows that problem hasn’t gone away in the C21st century*. The servants have their eyes on Lyte’s sheltered hedges in the knot garden as ideal places to drape garments to dry. Lyte flatly refuses. “I am not having that prime hyssop made buckled and drooping for the sake of undershifts and aprons.” He finds it bad enough having drying ruffs on sticks in the garden, looking sinister like empty white flowers (though he’s proud that his household uses cuckoo pint to stiffen linen and not cornstarch that could be used for food). The next morning he about turns over hedges and washing – there are no clean shirts – all are still damp.

Cruÿdeboek by Rembery Dodeons (from The Knot by Jane Borodale; Harper Collins, 2012)

The herbal is finished and on the press in Holland. Lyte’s aim was never to be original, although his notes on the Dutch text suggest he has learned much which he must have been tempted to add. He sees his English herbal as being a reference for people not able to pay for a physician. A bit of a workaholic, now the book is done with, his living garden, which can never be finished, calls.

Cruÿdeboek by Rembery Dodeons (from The Knot by Jane Borodale; Harper Collins, 2012)

Pervading the book is the fear of inundation of the Somerset levels. Lyte’s wife Frances never joins him on his journey to these fertile wetlands for she fears she will be standing on the bodies of drowned men. Frances died in 1589. In the year of Henry’s death 1607, a devastating tsumani, saw the sea breach land defences and waves of 10-12 feet surged up the rivers, flooding the Levels and killing many. Bodies float by in the water. Lyte reflects that Frances was right – after this he will never be able to eat eel, crab or any scavenger fish.

Cruÿdeboek by Rembery Dodeons (from The Knot by Jane Borodale; Harper Collins, 2012)

Curious connections – cause or coincidence?

John Aubrey, who discovered the stones at Avebury, was the grandson of Isaac Lyte of Lyte’s Carey.

Sir Walter Jenner bought Lytes Cary in 1907 inspired by his brother, Leopold’s restoration of Avebury Manor.

Cruÿdeboek by Rembery Dodeons (from The Knot by Jane Borodale; Harper Collins, 2012)

*Daughter No 1 announced recently that her children would do their own washing as soon as they were old enough. Get a second washing machine, then, was my terse reply!

Unicorn in meadow (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

6 Comments

I love the unicorn in his millefiori meadow, and the book sounds fascinating, and well-researched and written, too!

Thanks, Rachel. Glad you like the little unicorn.

When I started the book I didn’t think it would be as enjoyable as I ended up finding it.

Wonderful post, Mary. I have always loved unicorns probably from growing up surrounded by medieval illustrations. Yours looks particularly friendly. The book sounds very interesting (as all the books you review do) I have it on my list for next winter. There seems so many interesting people to investigate. I sometimes wish I lived in the age of Leonardo Da Vinci and could reasonably aspire to know all there was to know.

You’re so right, Anne, there’s so much to get interested in and such brilliant books to whet your appetite about things you never dreamed you might want to know. (At the moment I’m deep into a rather heavy book about exceptional books, The World’s Most Remarkable Manuscripts by Christopher de Hamel, librarian at Corpus Christie College, Cambridge – a lively and jolly read about a subject that could have been dry as dust!)

Now that sounds like something I MUST read

If you’re interested in the period and Elizabethan horticulture, this is certainly a good read, Anne. (And well written too.)

One Trackback

[…] though I think those aspects completely bypass the little girls that adore them so much today. Here is one I embroidered […]