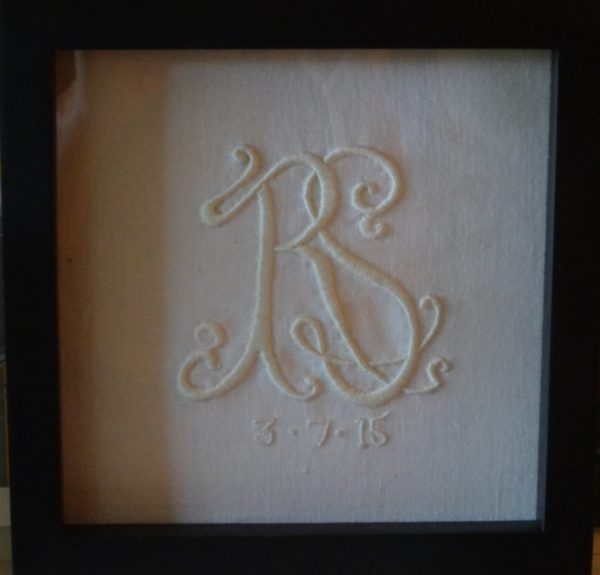

Embroidered letter R (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

This letter R is completely the wrong style to be associated with one of the worlds’ greatest potters – comic strip frivolity laughs in the face of classical elegance. But there you go that’s what happens when the imagination hops and skips its own way through life without as much as a sideways glance at the diary. The need for a colourfully striped letter had been creeping up on me for some time and it’s just plain unfortunate that it overwhelmed me in the week that I’ve been much taken with Wedgwood – the man, the museum, the pottery and books about him.

Embroidered letter R (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

We’d had this trip to the Potteries with The Friends of The Wilson (Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum) booked for some months but I don’t think my husband was overly eager or particularly engaged. A terrible journey up the M5 and the dreaded M6 which included a car broken down in the fast lane, road improvement works and lashings of some of the worst rain of the year, thanks to storm Diana, left me in lowest common denominator mode of comforting, “well, at least you’re not driving” and “just look, how well you can see over the hedges from a coach”! So, thank goodness for a brilliant talk by the museum’s archivist and an excellent lunch in the museum’s restaurant.

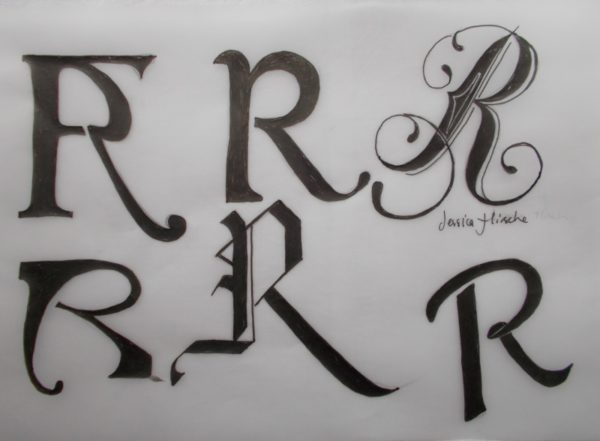

Sketches of various Rs found online

But first, a little digression. A cause célèbre a few years ago, the Wedgwood Museum went from glorious new launch and successful operation to threat of closure within just a couple of years. Legislation to protect employees’ pensions after the Robert Maxwell scandal meant that when Waterford-Wedgwood Potteries went bust in 2009, the high court ruled that the museum collection was an asset and should therefore be sold off – even though the museum had not been linked to the company for almost 50 years. Under pension plan law, because 5 of the museum’s employees were in the company pension plan, the full pension debt (of £134 M for 8,000 pensions) could be transferred to the museum. In a great hurry, £13 M was raised by the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund and a number of private trusts and foundations; a public appeal then raised the final £2.74M from more than 7,000 individual donations in a matter of months. The collection was saved and then gifted to the V&A. Hooray!

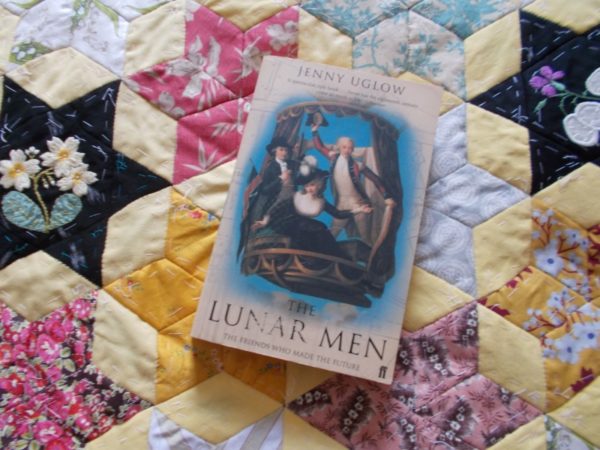

RS monogram (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

And it is a glorious collection including successful and unsuccessful attempts at The Portland Vase, items from Catherine the Great’s Frog Dinner Service (only those on which mistakes were made and which therefore didn’t go to Catherine) ), 2 of the first 6 vases Josiah Wedgwood threw himself to mark the opening of his factory and all those trays of experiments with the firing, colouring and glazing of clay. Have a look at the museum’s website if you love pottery, or better still get a group together and visit for yourself (talks are only arranged for group visits but are so worth having for the illustrative slides and the snippets from the archivist about all sorts of research that has been done and the fascinating questions she has to delve into the archives to answer). You can also walk through the factory on a high level walkway – but we didn’t do this as we just didn’t have time!

Jenny Uglow : The Lunar Men: The Friends who made the Future (2002)

The pottery I love but what also fascinates me is the spirit of the time and the intellectual climate in which the new ideas of the industrial revolution flourished. Josiah Wedgwood was a peripheral member of the Birmingham Lunar Society, an informal gathering of no more than 14 men who met on the night of the full moon. I call him a peripheral member because the journey from home to the meeting was comparatively long and arduous which meant he couldn’t always make it; even when he did get there he used the public mail coach so he had to take his leave of his friends at about 4pm to be certain of being home by midnight! Few of the Lunar Group had any formal higher education and anyway as the majority were nonconformists, England’s only universities, Oxford and Cambridge, would not have admitted them. Their study of science thus came from itinerant lecturers that crossed the country, study at universities abroad or in Scotland, and their own experimentation. Matthew Boulton, the son of a Birmingham metal worker, and Josiah Wedgwood whose father and grandfather had been potters were both hands on, intellectually and creatively gifted and driven men in whom the practical was for ever feeding back into the theoretical. It is salutary to note now how little scientific work was done at Oxford and Cambridge at this time where a classical education was still deemed the only course of study for a clever young man. Meanwhile science, blossoming in the provinces through the the lunar societies and in the dissenting academies, was as important a raw material as coal in the fuelling of Britain’s industrial revolution. Now I know that we have my own dear Church of England to thank for Balliol Library stacks being full of volume upon volume of Greek in translation and very little at all in the way early forays into science. Oh dear.

A.N.Wilson’s The Potter’s Hand (Atlantic Books, 20120

To learn more about the Lunar Society, get a copy of Jenny Uglow’s excellent non fiction The Lunar Men: The Friends who made the Future (2002) which I’ve recommended before. If you like your history laced with fiction, A.N.Wilson’s The Potter’s Hand (Atlantic Books, 2012) could be the book for you. I find a bit trying Wilson’s cod psychoanalysing of Sally Wedgwood’s depression and borderline frigidity (She had had 9 children!) and Wedgwood’s nephew Tom Byerley’s sexual adventures with Blue Squirrel, an invented Cherokee girl, he meets while negotiating buying white clay for his uncle from the indians and at first I was sceptical about the family of low born individuals he invents who are close to the Wedgwoods and who seem to understand them better than they do themselves, but I can appreciate such devices are useful to the novelist and help the narrative. However, I’m making these quibbles sound more important than they are for on the broad front, the book is a novel of ideas about a time when science, politics, philosophy, literature, religion were all undergoing a reformation – and in some cases formation. Famous people of the time pop in and out of the books pages as their paths intersect. As no story can be told in ideas alone, at the heart of the book is the story of a family and the painful lesson of wealth. Of Josiah Wedgwood’s eight children, four were boys and raised as gentlemen whose heads were filled with ideas not unrelated to their wealthy state but not wholly compatible with the successful running of their father’s business. Yet Wedgwood pottery carried on. The Wedgwood dynasty did even better and through prolific child bearing and marriage become a sturdy part of the backbone of English intellectual life pouring out more Wedgwoods, Darwins and Galtons and including individuals like artist Gwen Raverat and musician Ralph Vaughan Williams. A rich heritage in so many ways.

6 Comments

Gwen Raverat’s “Period Piece” (I think that’s the name) has some lovely little vignettes of her Darwin relatives, too…

Sorry, should I be recommending more books at this time of year?

Yes, Period Piece is a really good book for holiday reading with lots about the Darwins and Galtons, though very sad about her and her husband’s life.

Thank you Mary for another very interesting post. I learn something new every week! I love your colourful R

Thank you Nella for saying such nice things.

Another delightful post from which, as usual, I have learned more than I knew before. When I saw your “R” I thought of patchwork and mosaics. I think, whilst it may not have been to Josiah’s taste, some jolly dissenting Lunar Society gentleman would appreciate a very rollicking “R”.

Thanks, Anne. Glad you enjoyed the post.