Band of folk embroidery (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Before the beginning of the Second World War, Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London, had the foresight to despatch the gallery’s permanent collection of paintings to storage in North Wales. In fact, the first batch of 50 paintings arrived in Bangor on the 30th September 1938, the same day that Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler signed the Munich accord. With the imminent prospect of war averted, all 50 paintings were turned round and promptly sent back before the day was through. No doubt conservators had their heads in their hands as so much journeying was probably not incredibly good for the paintings but as a dress rehearsal, it must have been invaluable; within the year it was clear that war was unavoidable. This time all paintings were packaged up and sent away for safekeeping, mostly to various destinations in Wales, the lion’s share going to Manod Quarry, an abandoned Slate Mine in Snowdonia.

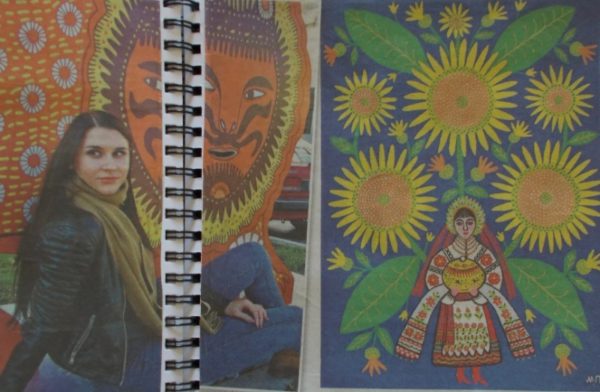

Maria Prymachenko, Ukrainian folk artist (1909-1997)

Clark was fortunate in that he had warnings of what was to come. The Ukraine had little idea of what was in Putin’s mind and even when western intelligence reported a build up of Russian military equipment on their most vulnerable borders, there was hope that it was military manoeuvres, sabre rattling or, at the worst, there might be an attempt at a rapid and limited incursion. Instead, with little notice of the enormity of what was to happen, as bombs and artillery rained down indiscriminately on the Ukraine’s cities, feverish work has gone on to try to save the most important art and artefacts of Ukrainian culture. The city of Lviv, a Unesco world heritage site has cleared its museums, galleries and churches and sent irreplaceable treasures to secret locations – for many, which have survived multiple wars, this was not the first time. Statues, like Odessa’s statue of the French Emigré, the Duke of Richelieu have been encased in a pyramid of sandbags. Richelieu fought for the Imperial Russian army, governed Odessa from 1803 to 1811 and went on to twice be French Prime Minister. His statue has survived the Crimea War, two world wars and numerous civil wars. Special attention has been given to items of Ukrainian heritage as the fear is that Putin will destroy those wilfully, especially where they contradict his distorted, not to say inaccurate, historical perspective. Some Soviet items have been left in storerooms or in some cases on display – a bust of Lenin (not even a favourite of Putin who blames him for Ukraine’s self determination) sits firmly on a window sill at the Andrey Sheptytsky National Museum along with other communist grandees.

Left: Anastasiia Prymachenko, the artist’s great granddaughter

Right: Maria Prymachenko – May I Give This Ukrainian Bread to All People in This Big Wide World

Unfortunately, Russian targeting of Ukrainian culture is all too real. Early on a Saturday morning at the end of February, Russian forces attacked a small town 30 miles South of Chernobyl and 50 mile North-West of Kyiv and shortly afterwards videos on Twitter showed a small squat building ablaze. This was the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum which, among other things had a collection of 25 works by Maria Prymachenko, one of Ukraine’s best known folk artists whose work Picasso and Chagall were much taken with. The museum was the first building the Russians destroyed when they entered the town. Fortunately they didn’t hang around and a local man was able to rush into the burning museum and collect as many of Prymachenko’s paintings as he could carry. The painter’s granddaughter Anastasiia, director of the foundation named after her great grandmother, thought he had saved about 10 poster sized paintings. The largest collection of Maria’s work, about 650 items is in the National Museum of Ukrainian Folk Decorative Art in Kyiv. Many more of her paintings are dotted around the Ukraine but sadly in areas where there is little or no protection.

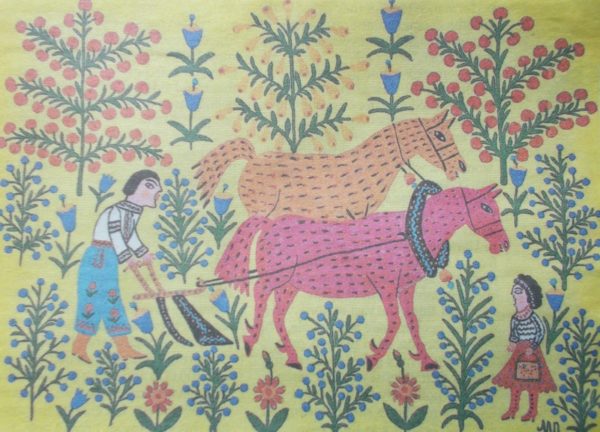

Maria Prymachenko: My Beloved Plows the Field

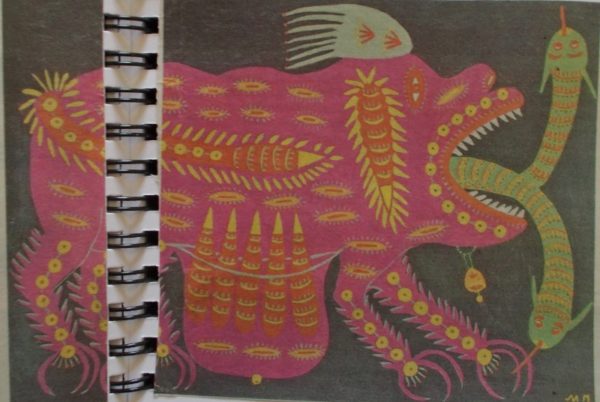

Picasso and Chagall first saw her work at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937 where her drawings were awarded a gold medal. Picasso was invigorated by what he saw, “I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian “, while Chagall described his own magical realist creatures as “the cousins” of her “strange beasts”. Rachel Campbell-Johnston (The Times 4 March 2022) describes Prymachenko’s symbolic works as belonging “to the hinterlands that lie between the mystifying and the meaningful.” On the one hand hand, she says, her work is full of very traditional symbolism (in which for example, a rooster stands for fire and spiritual awakening) while other paintings have texts on their reverse that point the reader in the direction of the mysterious and surreal (“Corncob Horse in Outer Space”). Prymachenko knew hardship and her own life had met war full on. Her fiancé was called up to fight in the second World War when she was pregnant. He never came back and she was left alone with a child to bring up. Her brother was shot by Nazis. Later paintings, especially those made when Brezhnev was leading the USSR are anti war. A bright pink and yellow lion-like animal (See picture below) is decorated with missiles and warheads, while strings of grenades terminating in claws like grappling hooks stream down its limbs. From the beast’s mouth two serpents emerge and promptly diverge to spread wider death and destruction. Maria’s title for this this painting is “May That Nuclear War Be Cursed”!

As I finished writing this, I’ve just checked the news to discover the Russians have bombed an art school in Mariupol.

Maria Prymachenko: decorative plate thought to have been lost in the museum’s bombing

Maria Prymachenko: May That Nuclear War Be Cursed

2 Comments

It’s horrifying and bewildering in equal measure, especially when there is so much that’s wonderful that is either at risk or already destroyed. I think we who make things are particularly baffled by the impulse to destruction.

Couldn’t agree more, Rachel. We are so blessed to live in a country that has experienced comparatively little of the destruction of war.