Sweatshirt with appliquéd and embroidered salamander (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Christmas in the Lakes for my daughter’s mother-in-law must have been an exhausting time, what with catering for half her family quarantined away at the top of her house, as well as presumably washing their clothing, bed linen, towels, etc., let alone generally worrying about their limited access to all the seasonal pleasures enjoyed by those in the house below. After 2 years of waiting to see family, how galling must it have been to have half her family there yet not there! If ever there was a woman who truly deserved a good book to get lost in for a few days in January, this was she. A brief enquiry through her son revealed she had read (and loved) the first book I had in mind, a novel, (Amor Towle’s A Gentleman in Moscow), so I just emailed her direct with my next choice, The Pinecone, by Jenny Uglow. Happily she hadn’t read it and like me, was a great fan of the author, whose Lunar Men is one of my – and her – all time favourites. The Pinecone, however is at the other end of the scale from The Lunar Men. Where the latter is an ambitious multi thread biography of men who set alight the blue touch paper firing an incendiary Britain clear out of its C18th agrarian economy and on into the industrial firmament of the next century, The Pinecone is a quieter book about a single and singular woman, Sarah Losh, who devoted her wealth and energy to serving her local village (Wreay, pronounced ‘rhea’ to rhyme with near) and to building for it a unique and strangely marvellous church whose symbolism celebrated Nature in its diversity just as loudly as Christianity.

The Pinecone by Jenny Uglow (Faber & Faber pub. 2012)

Sarah Losh’s wealth came from her family’s discovery of an industrial process for manufacturing alkali – a commodity that most of us have never given any thought to but which underlies a myriad of important industries, including glass making, soap making and the bleaching of textiles. Sarah’s philanthropic work involved the building of wells, cottages and a village school all in a unique style which culminated in her architectural and decorative design of a new village church. The symbolism was all Sarah’s own, epitomised in the book by the pinecone whose ancient associations with regeneration, fertility and inner awakening she happily seized upon. Skilled mathematically, though largely self taught, she understood that the bracts of the pinecone whorled around in opposite directions from the base up according to a pattern dictated by the Fibonacci series, a manifestation of what she regarded as the ‘Sacred Geometry’ of nature. In the church pinecones are to be found all over – carved in wood hanging from roof trusses and as an ingenious door latch on the main door as well as in stone, where they are recurring motifs around the window arches.

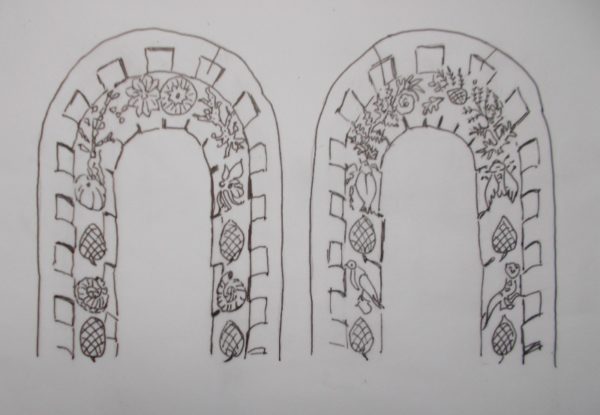

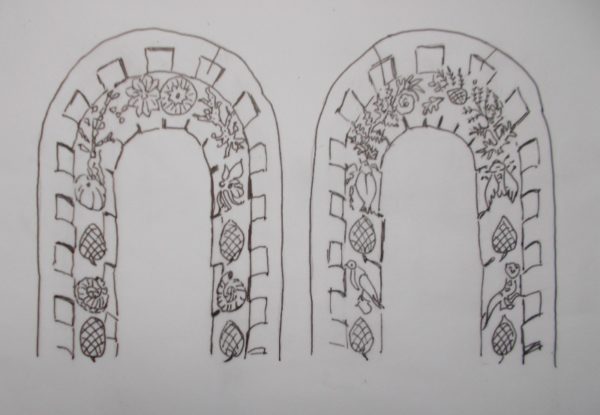

Sketches of carved windows from St Mary’s church Wreay

In structure the church at first resembles a cross between a simple Romanesque basilica (a bit like the sort you see on islands like Torcello in the Venetian lagoon) and a Lakeland farm building (admittedly a rather splendid one). But the closer you get, the more extraordinary it seems. Instead of sentinel saints and prophets, ancient animals and plants crawl and curve their way around the window embrasures (see my sketch above). For gargoyles, (though not acting as gargoyles) there is a winged friendly looking turtle, a dragon, a snake (half serpent, half plesiosaur), an open mouthed crocodile and a tortoise seemingly in the middle of throwing itself off the building! While the dragon acts as a vent for the boiler in the nave, the other four beasts function as ventilator covers. How splendid the smoke breathing dragon must have looked on Sundays !

Sketches of clerestory windows from St Mary’s church Wreay

Inside, the building really comes into its own. Church furnishings are unique to the point of idiosyncratic and bizarre – the alabaster font has a mirrored lid on which alabaster water lilies float, there are two lecterns, one a conventional eagle, the other an energetic stork, while elsewhere carvings include symbols and gods from other religions and even cults. Predominantly though, most of the decorative elements celebrate the natural world – both living (butterflies and sea creatures like the nautilus,) and ancient in the forms of carvings of comparatively recently discovered fossils like ammonites, fossil ferns and strange insects.

Sketches of clerestory windows from St Mary’s Church Wreay

But for me it’s the windows that fascinate. The larger windows, 3 on each long side, are geometric in general layout with shards of clear glass in the central panels while coloured fragments nudge each other along in the border. These are lovely but above them, come 3 groups of 3 little clerestory windows and it’s these I find particularly gorgeous. The top third of most of these windows is composed of a coloured glass roundel filled completely by the head of a single flower (rose, lily, poppy) while beneath this, higgledy piggledy shards of coloured glass jostle along together to support and enliven the bloom. Photographs of these little windows remind me of Victorian crazy quilts in which occasional large pieces of fabric carry embroidered flowers in a sea of tiny and often beautiful precious pieces, whose pattern is no longer clearly visible. I’ve hunted online for images of all these windows and because I couldn’t get enough of them, I tried to copy the few images I found as a way of enjoying them more. Their enchantment is enhanced by the knowledge that, like their patchwork cousins, some of these fragments were recycled – either saved from other sites or even picked up from off cuts beneath the craftsman’s feet; flicks of unfurling leaves, bits of tiny faces, broken crosses and even a portcullis hint at parts once played in completely different stories. This recycling strikes a surprisingly contemporary note but one which chimes in with Sarah Losh’s idea of the evolution or resurrection of buildings, whether in terms of style or materials used.

Sketches of clerestory windows from St Mary’s Church Wreay

Perhaps the most spectacular re-use of fragments is to be found in the East window on the North side where there are pieces of glass Sarah’s relative William Septimus had picked up off the ground in Paris during the 1830 Revolution when windows in the old archbishop’s palace, the C15 th Hôtel de Sens, were shattered during fighting. Carefully stored away for ten years with no thought for their use, William Septimus brought them out for Sarah’s new church.

Sketches of clerestory windows from St Mary’s Church Wreay

Owing to certain bureaucratic mishaps in the buying of the book, I actually ended up with 3 books. The full price one I sent off to the Lakes and I kept one to read myself. Then, when a friend who came to make sure I didn’t do anything silly after being sedated for my tooth extraction oohed and aahed at the book, it seemed only right to send her the third to say thank you. I’m not sure I’d recommend the book generally. The first half is devoted to a detailed history of Sarah Losh’s family and the social history of the time and although forays into who knew Wordsworth well and what happened on The Grand Tour are interesting, they aren’t quite what you expect from a book entitled The Pinecone. Books describing buildings are always difficult without lots of pictures and when I read this part I had my computer open and trawled numerous sites to find images of details discussed. It’s funny that I started the book with no real desire to see the church but then as I read on and searched in vain for detailed pictures, especially of the windows I was overcome by the desire to make a visit. My daughter’s mother-in-law (isn’t there an easier way of describing this relationship?) lives near Lake Windermere and I fancied I was giving them an ideal destination for a afternoon out. It was only when she pointed out that Wreay is probably about 70 miles from them (and best reached by the M6 motorway) that I realised I was making a classic southerner’s mistake of misjudging distances the further north you go!

Salamander appliquéed and embroidered on sweatshirt (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Last week my husband was to give the second of a group of four art appreciation sessions at Chapel Arts, a private gallery in the centre of town. Numbers had swollen to nearly 40, sufficient information sheets were printed (unlike the week before), the sophisticated projector system was playing ball … and then there was a power cut!

This week’s sweatshirt has an embroidered salamander – and I wouldn’t be surprised if Sarah Losh’s church has one too!