I seem to have taken another week off from blogging and this time I’m going to be very British and blame the weather. It was one of those weeks in every month when David had 3 Art Appreciation Sessions and honestly walking into town, looking at images of paintings, exchanging ideas about them and then getting home again, was just about all we could cope with on those three days. The British, having no tradition of siesta during hot weather, are thrown out of kilter by the sort of heat we’ve had recently, especially if your timetable is such that you find yourself setting off from home or returning to it just when the sun is at its highest. Rather than complain, we just gave in and did everything much slower than usual. The upside is that washing on the line outside has dried in no time. If it continues like this much longer I shall strip the loose covers off the sofa and give them a much overdue laundering.

Susan Sontag: The volcano Lover (Pub. Vintage 1993)

Now to The Volcano Lover, by Susan Sontag, a terrific beast of a book, part history, part drama and part feminist tract – feel free to roll your eyes wearily now – except you don’t have to because it’s bang on what you ‘re thinking to yourself as you read the book anyway. In structure the book’s a bit wobbly and all over the place but in essence it tells the story of the intertwining lives of 3 historical figures, none of whom are referred to by name (a bit like Hilary Mantel in Wolf Hall who never (? I think) refers to Thomas Cromwell as Thomas Cromwell, just ‘he’). Sir William Hamilton, diplomat, volcano watcher and Greek pot obsessive, appears as the Cavaliere. His second wife, Emma, a charismatic, C18th performance artist, as clever and accomplished in the art of pleasing men as she is in as yet unplumbed intellect, takes her place as the Cavaliere’s wife while the third protagonist, known simply as the Hero, is Lord Nelson who, taking a break in Naples after his successful Egyptian campaign, involves himself quite unnecessarily in one of the most notoriously bad decisions of his career. Using titles for the characters instead of their names may sound clunky but on the page they work well and distract the reader away from some of the unnecessary baggage of their historical reality so you dig down into the person beneath. Interestingly, the focus of the novel is on Sir William (collector and cuckold, the least charismatic of the three) which is as clever a move as it is unexpected.

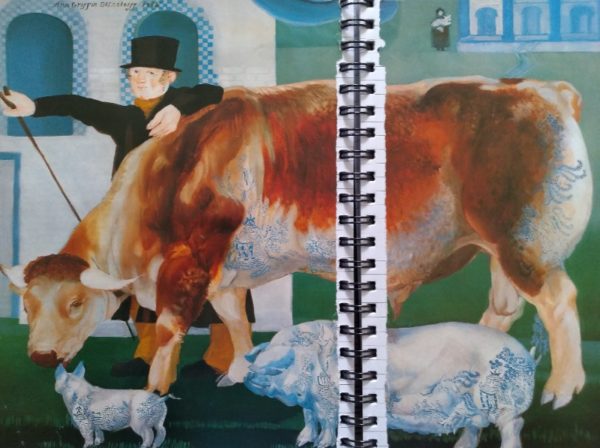

Sir William Hamilton had been British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples from 1764 (formally his title was Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies). His job was to report back to London and liaise over local concerns with Ferdinand, the King of Naples, a dysfunctional Trump like figure whose single and almost insatiable desire in life was to be out on the hunt, killing as many innocent animals as his servants could funnel in his direction (often accompanied by the aesthetically sensitive Hamilton.) Meanwhile, his subjects starved in the streets. Fortunately, or unfortunately as things turned out, his wife, Queen Carolina, daughter of the formidable Hapsburg Empress, Maria Theresa of Austria and sister to Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, had brains for both of them (although sadly insufficient wisdom for even just herself). The milk of human kindness was somewhat lacking in her too. Emma Hart (formerly Amy Lyon, later Lady Hamilton) makes her first appearance in the story as piece of decorative baggage handed on in part payment of a debt to Sir William by his nephew. The attractive hand luggage, clever and eager to be educated rapidly advanced to protegée, through to mistress and after a few years to loving wife. To Queen Maria Carolina she became confidant, occasional spy and sometimes the instrument of her royal will.

Hamilton’s professional career in Naples had for many years been parked in a bit of a cul-de-sac. He had hoped for a more exciting posting to come his way – Moscow perhaps – but as it became apparent this would be unlikely he solaced himself by collecting fine art, antiquities and especially the splendid Greek Vases (often misnamed Etruscan) which were emerging from the excavations of places like Pompeii and Herculaneum. While his house filled with vases, the volcano that had buried them proved equally fascinating and soon his scholarship stretched from commissioning books depicting his vases to academic papers for the Royal Society in London analysing volcanic rock and documenting Vesuvius’s pyrotechnics.

As the old century came to an end, Naples became politically increasingly unstable. Earlier in the 1790s Napoleon had put a relative on to the throne causing the Neapolitan court to retreat to Palermo. A deal was done and they returned. When the French withdrew troops from Rome, Maria Carolina sensed an opportunity for expansion and sent King Ferdinand north to take possession of it. The French promptly counterattacked and, the hunter hunted, Ferdinand scurried back to Naples, where, fortunately for him, he found Nelson fresh from winning The Battle of the Nile and willing to load up his flagship with the ridiculous paraphernalia of the court for a second retreat to Palermo.

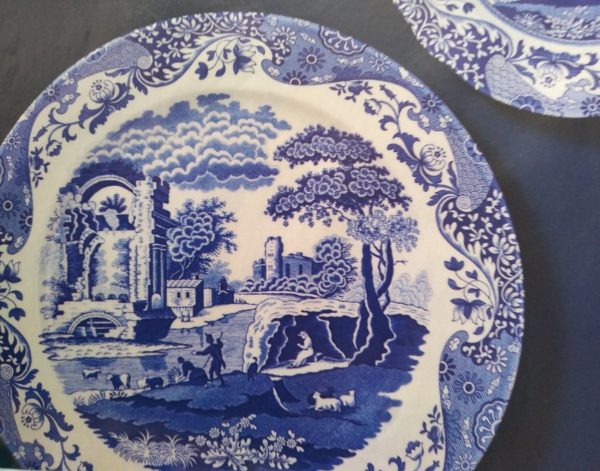

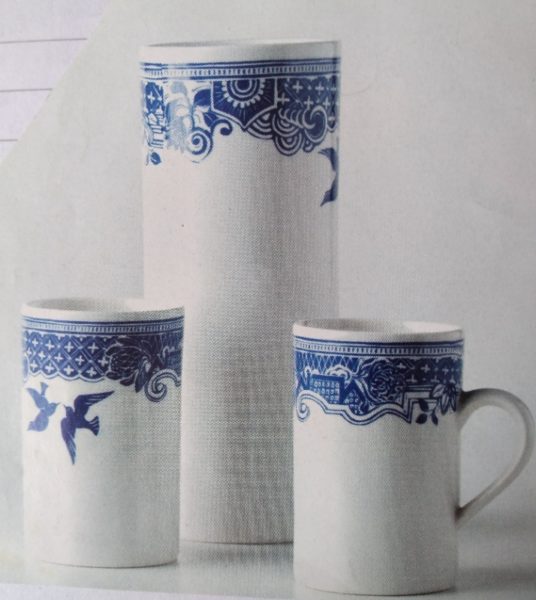

Copy of Portland Vase (possibly C19th Copeland)

At the heart of the book is the summer of 1799. Naples had been recaptured from the French and the court at Palermo were pushing for severe reprisals against those revolutionaries in Naples who had set up the short lived Parthenopean Republic. Cardinal Ruffo, in charge of anti-Republican forces negotiated a capitulation with the revolutionaries according to which castles were to be emptied of troops, hostages were to be set free and troops were free to stay in Naples or were to be allowed to sail to Toulon unmolested. The capitulation was signed by Ruffo, and British, Russian and Turkish officers, as well as the Republicans. Nelson then sailed into the Bay of Naples (with no Neapolitan court officials, only the Hamiltons on board in their capacities as diplomat [Hamilton] and interpreters [both]). Nelson moved quickly – not only did he refuse to honour Ruffo’s deal but, even worse, prompted by the known desire of Queen Maria Carolina, he demanded retribution from the revolutionary (i.e. republican) leaders, pre-eminently, Prince Francesco Caracciolo, the admiral of the Republican fleet who had been discovered disguised in a ditch just days previously and brought on board Nelson’s flagship. Swiftly a court-martial was set up in accordance with few of the written and unwritten rules of war. The guilty verdict came quickly reeking of a preordained judgment and execution was ordered. Within 24 hours Caracciolo was hanged from the yard arm of the British ship Minerva. It was a shameful act by Nelson (later denounced by Charles James Fox in the house of Commons). It’s interesting reading Sontag on this alongside Jonathan North’s book Nelson in Naples, Revolution and Retribution in 1799 which looks at the events of this time in finer detail. What horrifies in Sontag’s book is magnified in North’s and, with the proviso that Lady Hamilton was possibly not as influential in Nels0n’s actions as Sontag makes out. Both books, however, leave the reader in no doubt that this was Nelson’s most dishonourable hour.

On one level the book continues with the story of the famous threesome which Sontag follows through to their return to England, their reception there and ultimately their deaths. Hamilton’s meditations as he lays dying are well done and then Sontag turns from her eponymous hero to the women in her story, including some very marginalised figures inhabiting this very masculine world. Queen Maria Carolina is haunted by the nightmare of her sister Marie Antoinette’s beheading ever present before her when it looks like the Parthenopean Republic might take hold. Unfortunately the very real power she wields is vindictive and destructive Catherine Barlow, Hamilton’s first wife, an heiress whose money funds his insatiable collecting, is powerless in spite of her fortune. Happyish with Hamilton, Sontag can’t resist giving here a back story which includes falling in love with William Beckford who pays her more attention than her husband. (Some mistake surely as Beckford was a know homosexual?). The book ends with the diary entries of Eleanor de Fonseco-Pimentel, journalist-poet, idealist and political activist, admirer of the ideas of the French revolution and Mary Wollstonecraft, overthrower of the Bourbon monarchy and one of the leaders of the Parthenopean Republic. Of aristocratic origins, as a woman she was singled out for particularly harsh treatment and publicly hanged to be an example to others.

Revisionist history is often a very bad idea but Susan Sontag’s examination of much slandered Emma Hamilton through the lens of late C20th feminism is an exercise not all of which needs a red line through it.You could look at Emma as the girl who had the cake and ate it or you could regard her as a survivor who was always going to need a man in her life and was clever enough to make not just one man, but two sufficiently happy in their individual love for her that the three of them could live lives intricately intertwined together. Undoubtedly she deserved some masculine kindness. At 16, poor and beautiful, she became the mistress of a young aristocrat who abandoned her when she became pregnant. Then, Hamilton’s nephew made her his mistress on the condition that she had the child fostered, which she did. When married, she tried to persuade Hamilton to have the child with them, ostensibly as Mrs Cadogan’s (i.e. her mother’s) niece but he was deaf to her entreaties. When she falls in love with Nelson, she treads a delicate line between her husband and lover, carrying Nelson’s baby to full term, lamenting her weight gain, but making no mention of pregnancy to her husband. Somehow having given birth in secret in the Hamilton house in Piccadilly, she managed to keep the baby with her for a week and then bundle the child into a hackney carriage and on to a wet nurse in Little Titchfield Street where she was to remain until she can work out away to reclaim the child to her care as someone else’s offspring. I have a real soft spot for Mrs Cadogan. Throughout all but the first of her amorous affairs Emma’s mother, matronly Mrs Cadogan is at her side – whether dining with Hamilton’s aristocratic guests, nursing Nelson’s injuries after the Battle of the Nile, or taking care of Emma and her infant before the child was fostered.

Copy of Portland Vase (possibly C19th Copeland)

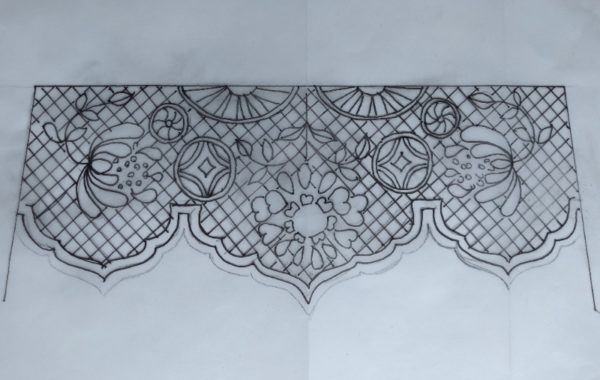

Running off the main trunk of the story come side branches of interest . There’s a cameo appearance of Goethe, a sad interlude concerning Hamilton’s neglected pet monkey (one of the biggest blots on Hamilton’s character, along with not managing to rein Nelson in), a digression on the Portland Vase (bought by Hamilton in Naples, sent to England to be sold, the gloriously copied by Wedgwood) and then the sudden, and utterly confusingly the reader is plunged into the middle of Puccini’s opera Tosca with Scarpia (a historical figure) and others the reality of whom I’ve yet to work out. It’s all too much.

Read The Volcano Lover and then go back and read it again. It’s a very dense book with not a boring passage in it and I have found it almost impossible to write about. Still I feel I have to have made an attempt. I haven’t found a sniff of John Rushout (after 1800, Lord Northwick) but I know a great deal more about what was going on around him. It was also very useful for me to try and work our exactly what was happening in Naples during those 6 months at the beginning of 1799 for John Rushout is there – but in Jonathan North’s book – even with his own words!

Oh, and in case I haven’t already said so, The Volcano Lover is also beautifully written.