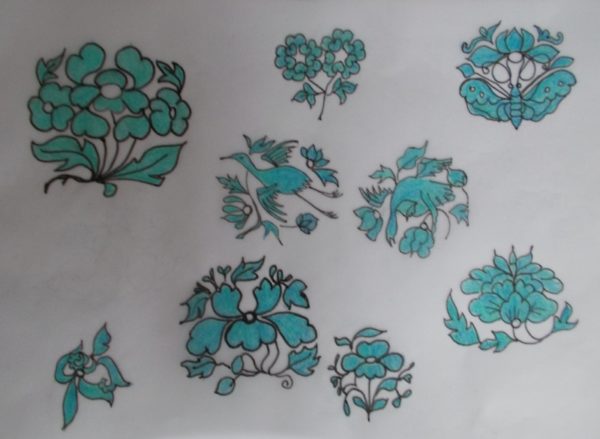

Embroidered longhorn beetle T shirt (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

And so begins my series of children’s T shirts destined to be presents over the next few months. After the feed back from the insect T shirts I made earlier this year, I know that insects go down well with older children but I’m no so sure whether toddlers will find them fun. If in doubt about form, go overboard on colour, I thought, and slapped a scarlet long horn beetle (of the family Cerambycidae) bang in the middle of a navy blue top.

Embroidery of long horn beetle (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

‘Long horn’ looks like a bit of a misnaming as the long filaments which together almost circle the entire body are not horns but antennae . Often when names are confusing and downright misleading, it helps to dredge the depths of classical mythology for an answer. And there you find the story of the Greek shepherd, Cerambus who tended his sheep on the slopes of Mount Orthrys. No ordinary herder of sheep, Cerambus was known for his glorious voice and lyre playing of such loveliness that it lured the usually unseen naiad nymphs of the mountain’s springs to reveal themselves to him as they listened. Vanity and arrogance took hold of Cerambus and soon he was gossiping carelessly about the nymphs, casting doubt on their origins and repeating a story they found most shaming concerning the time they were temporarily turned into poplar trees while Poseidon ravished of one of their sisters. Distressed, the nymphs in turn transformed Cerambus into a wood-gnawing beetle with long antennae which it suited the story tellers to describe as horns. And, even after centuries of entomological research, the horn description has stuck.

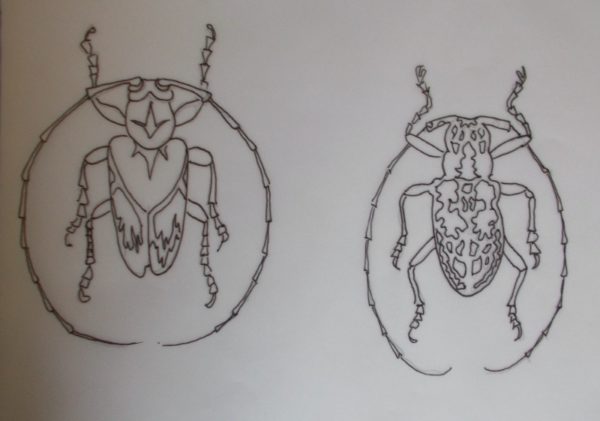

Sketches for longhorn beetle embroidery

I’m midway through The Fabric of Civilization by Virginia Postrel (pub. Basic Books, 2020). I’d asked for the book for Christmas last year but we’d been unsuccessful in our attempt to buy it via Selvedge Magazine. Then last week I saw it in Tetbury’s excellent bookshop, The Yellow-Lighted Bookshop, and swooped upon it doubly happy with both present and forgotten delight. The book is dense but incredibly readable and I think for the first time in my life the writer has helped me to envision in 2D how Damask weaving in 3D is achieved. (That is I get little glimpses of understanding through the text rather as light flashes in and out as the movement of slats on a Venetian blind .)

Embroidered longhorn beetle T shirt (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

On weaving in general Postrel is mesmerically enlightening. Contemporary handweavers use graph paper and even computer programs to record weaving patterns but as she points out affordable paper is a relatively recent resource and complex woven patterns go back milliennia. In the Odyssey, Circe and Calypso sing as they weave and we’ve probably all assumed they were singing the folk songs of their day just to amuse themselves but Postrel says their singing and chants were more likely encoding thread counts and colour changes. A C19th European traveller in Central Asia noted that rug weavers chanted “in a weird sing-song the number of stitches and the colour in which (new patterns) are to be filled”. This notion excited me for I find I do it too when working on Fair Isle bands – rhythm and a rhyme makes it easier to remember stitches and colour changes and even whether and when you should catch in the looping thread draping across the back of the design when one colour plays no part in the pattern for more than 3 stitches. Singing a row is always quicker and easier than referring back to a chart (though of course, it’s vital the chart is there in the first place – both to get you going and to refer to when someone asks you if you want a cup of tea!) Fascinating. This is a book to be read, then re-read and then, when there is time, to be read again with notes. I do like a good bed time thriller on the go, whether grabbing the odd half hour in the day or before going to sleep at night but this book is every bit as thrilling and just as difficult to put down – I only wish I could remember more of what I’ve just read!

Virginia Postrel: The Fabric of Civilization. How Textiles Made the World (pub Basic Books, 2020)