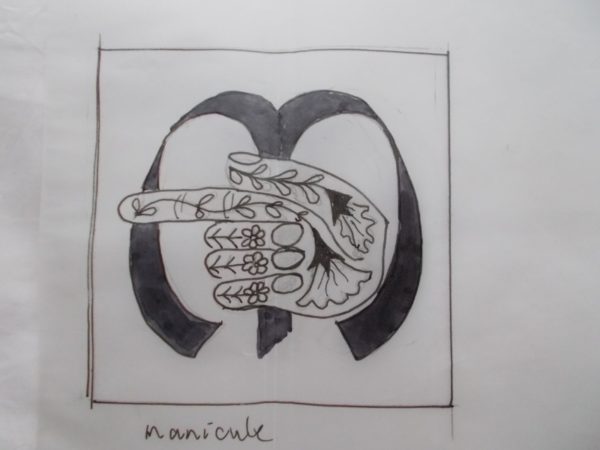

Whitework alphabet: N for nautilus (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Nautilus shells are things of great beauty but although I’ve borrowed the form of the shell a few times for embroidery, I’ve never thought about the animal housed in such gorgeous architecture. This time, my whitework N for nautilus has the whole animal – head, with prominent eye and some of the up to 90 tentacles. In spite of the arresting – and even intimidating – appearance of the eye it functions little better than a pin hole camera and, with no solid lens, its vision is pretty poor. Mathematicians love the shell as much as designers for it’s about the best natural example of a logarithmic spiral exemplifying the Fibonacci series that you can meet in nature (blogged about here with diagrams if you’re interested!) And with that I dried up, unable to think of anything more on the subject, until … I made the exciting discovery that a C19th uneducated embroidress turned naturalist had unlocked the secrets of the so-called paper nautilus.

Whitework alphabet N for nautilus (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

The first thing to say is that the nautilus, shell and animal, is not to be confused with the so-called paper nautilus. Similar shells house very different animals, both of the class Cephalopoda, but the paper nautilus is an octopus while the nautilus is, well, a nautilus. Further, the shell of the paper nautilus, thinner, more transparent (reminiscent of pleated tissue paper or Fortuny’s finely crinkled Delphos gown), is not strictly a shell (the animal doesn’t live in it and doesn’t rely on it for protection) but an egg case which the female starts making early on in life and then carries with her ever after. Initially, naturalists thought that the paper nautilus animal adopted shells much like the hermit crab, but, gloriously, in the early C19th, an uneducated French woman, proved otherwise. Jeanne Vilepreux-Power, daughter of a shoe maker, and a skilled seamstress and embroidress (she’d embroidered the wedding dress of an Italian princess), met and married an Englishman in Paris and settled in Messina in Sicily. Here, with more leisure and presumably no need to work for a living, she set about studying the paper nautilus.

Whitework alphabet N for nautilus (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

To begin with Jeanne determined that she would study the animals alive and to this end she experimented with various models of simple aquariums, including ones small enough for the domestic study while others, bigger, floated in the sea, anchored to the sea bed. Though Philip Gosse is credited with popularising aquariums, Jeanne is usually credited with inventing the first properly functioning one in 1832. From then on, she could watch young nautili develop and prove that they grew their own shells. She also observed that what looked like just another suckered arm in the egg case was in fact the diminutive male. Further evidence that the shells were of their own making came when she watched adult females mending damage to the shells, using secretions of calcite from specialised membranes on two of the many arms.

Drawing for whitework alphabet N for nautilus (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Jeanne met much opposition from the scientific community although she was fortunate enough to be championed by the eminent naturalist Richard Owen who challenged anyone questioning her findings in his hearing. Jeanne and her husband left Messina for England in 1843 and disaster struck when the ship carrying all her papers and specimens was sunk at sea. She published nothing further and it is only through her letters to other scientists that her work is remembered. In 1997 a large crater on Venus was named in her memory.

How wonderful is that? I started this post with nothing much to say and then discover there’s an there’s an embroidress underneath it all. For a little more about Jeanne Vilepreux-Power see here.