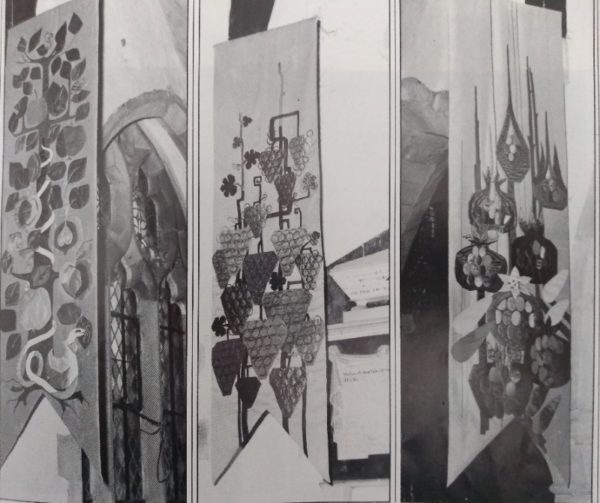

All Saints, Newland, The Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire. Also known as The Cathedral of the Forest. Photograph of the Lady Chapel resplendent with 4 glorious embroidered and appliquéd banners and patchwork altar frontal and hanging. All work was done by Beryl Dean and her team in the early 1980s.

Later this month I shall quietly celebrate 10 year’s almost unbroken blogging (with a few blips due to moving houses or family commitments). I know many fewer people have time for blogs nowadays but that doesn’t bother me as I realise it has become important to me as an extended letter to my grandchildren to be read at some point a long time hence. (And in case the internet is made obsolete by some as yet unthought of means of ultra sophisticated communication, my husband has been so kind as to regularly concern himself with printing it out.) I could now no more stop blogging than I could stop cleaning my teeth – or perhaps as it’s a weekly thing – washing one’s bedlinen would be a better analogy.

All Saints, Newland Gloucestershire: Banner in lime green of the serpent in the apple tree. Designed by Sylvia Green and worked by Mary Brooks under the overall direction of Beryl Dean

It is therefore quite odd to realise that in 10 years I have failed to mention the biggest embroidery project with which my family has been involved. The next few posts will put that right. But first let me put things in a rather lengthy context.

All Saints, Newland, Gloucestershire: Banner with pomegranates in apricot, pinks and greens. Designed (and I think worked) by Beryl Dean. Behind is a banner in sea greeny-blue with ears of wheat, also produced under the direction of Beryl Dean

After nearly a decade as director of the museum and art gallery here in Cheltenham, while simultaneously being a Church of England curate at Bisley above Stroud, in 1981 Rev. David Addison, (my husband, from 2007) decided he had done as much as he could in curatorial and organisational terms for the museum and that it was time for someone else with different interests and skills to take over. His achievements included staging many varied exhibitions, instituting regular lunchtime talks about the collections and the setting up of what was then known as The Holst Birthplace Museum. The latter had the twofold benefit of not only being a visitor venue as a period property typical of Cheltenham’s C19th house building boom but was also the fitting home for Gustav Holst’s bequest to the people of Cheltenham ( a bequest which had languished homeless for many years in store in the museum). From full time director of the art gallery and museum, David moved to full time vicar of what the Bishop of Gloucester called “a couple of difficult parishes in thee Forest of Dean”. The two parishes embraced 3 churches – All Saints, Newland (a splendid building also known as The Cathedral of the Forest, dating from the early C13th), St Saviour, Redbrook and St Peter Clearwell. Both the first two churches had been severely neglected, while fortunately St Peter, Clearwell, a C19th church by Middleton, was in good order.

All Saints, Newland, Gloucestershire: Banner with bunches of grapes and vine leaves in tones of purple and mauves. Designed by Hazel Sims under the overall direction of Beryl Dean

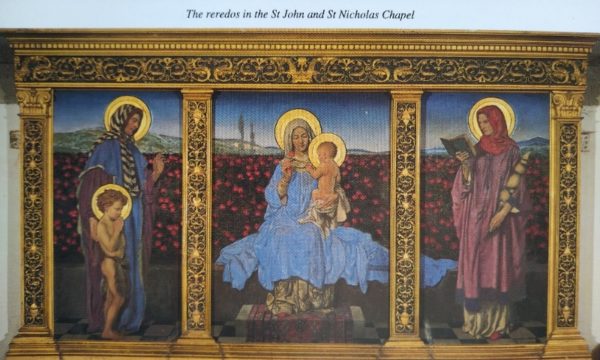

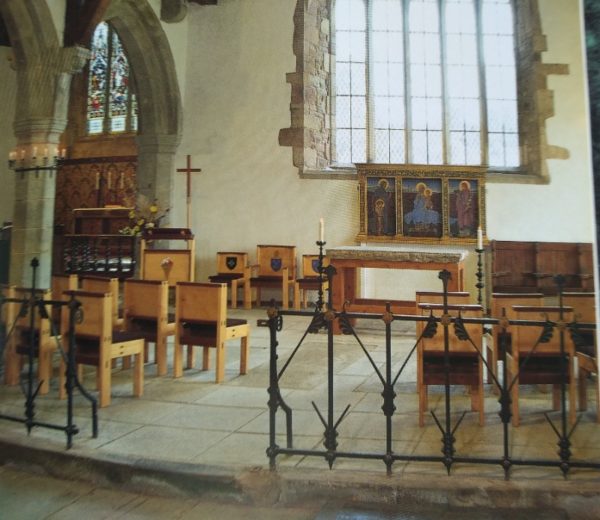

There was much to be done and David set about the practicalities of the job in much the same way as he had with the museum and art gallery – that is he wrote a report. Neither church was weatherproof, windows were broken and the roofs had leaky areas and outright holes. In Redbrook church, trees and brambles had pushed their branches through the holes and in their new environment, they seemed to be flourishing. The main door opened just enough for visitors to squeeze through, so that the first funeral David took in the church involved the undertakers having to do a good deal of pushing and shoving to get the coffin in. Meanwhile, the organist grappling with a decrepit organ sat over a big hole in the floor which she ignored at her peril. Newland church, quite different from Redbrook, had a fine broad open layout with no fixed pews but its bare boned beauty was marred by the big chapel (dedicated to St John and St Nicholas) right next to the high altar whose badly broken stone floor had become a depository for piles of miscellaneous stone slabs, including 3 altar tops and numerous memorial tablets of varying ages. The chapel’s very large east window of clear glass had a big area with no glass at all (the original stained glass having disappeared long ago) while an almost unplayable organ inadequately covered by an untidy canopy of tarred felt sat directly beneath holes in the roof. In the midst of this ruination, precariously perched and insufficiently protected (and in front of the badly broken window) stood a beautiful but very dirty triptych of the Virgin and Child with Saints painted by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale. (Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, 1872-1945, one of the golden age female illustrators, was an important member of the Birmingham School and considered to be the last survivor in the line of the Pre-Raphaelite tradition.) Few church furnishings had survived and there were no vestments apart from a few very run of the mill stoles. David submitted his report with estimated costing to the relevant church bodies and was pleasantly surprised to find that it was approved. He later discovered this was because no one expected funding to materialise and in rubber stamping the report they could be seen to be doing something positive.

A closer look at the beautiful lime green banner with a clearly sly serpent in the apple tree. Designed by Sylvia Green and worked by Mary Brooks under the direction of Beryl Dean

Now, one of the many thought provoking things about David’s professional life is that when money was needed, it often turned up. A few weeks after submitting his report, he received a letter from a solicitor on behalf of the estate of a recently deceased woman, the last remaining member of the family who had owned the Redbrook Tinplate Works. Hospitalised for some years, David had never met her but her memory of Redbrook and Newland churches must have been strong for she left a large sum of money to be spent on the churches “at the Vicar’s discretion”! In fact the large sum of money was just about the amount that David had estimated for the repair of both churches. I shall not go into what happened next, but must skim over a difficult time during which the money quite simply disappeared into corrupt hands. That it came back – almost in its entirety, albeit in dribs and drabs – was nothing short of a triumph of quiet amateur sleuthing and patience, with possibly the touch of an angel’s wing to help it on its way…

All Saints, Newland, Gloucestershire: Black and white photograph of 3 of the banners in the lady Chapel (made by Beryl Dean and her team) Photographtaken from Embroidery magazine Spring 1984 (v.35, No 1)

Beside David through all these vicissitudes was his wife Joy who was his touchstone, rock and uplifter of spirits when things seemed so very dark. Joy died more than 5 years before I ever met David and I find it quite difficult to get a real picture of someone whose path you never crossed. So, how wonderful is it that both of David’s wives shared a passion for embroidery. Joy had studied at Goldsmiths College, London where Beryl Dean (1911-2001) a, if not the, leading exponent of modernist design in church embroidery, had come as a guest lecturer. Many years later, as David and Joy were setting about restoring the churches, Joy remembered Beryl Dean’s inspirational talk and decided to write to her to see if she was interested in designing and making something unique for Newland church. Very quickly a polite letter came back saying that she couldn’t help. Then, a week later, another very emotional letter landed on the vicarage’s doormat. Full of apologies, Beryl said Joy’s letter had touched a nerve, got under her skin and that she had hadn’t been able to sleep since she’d sent the first letter. On reflection, she felt sure she could help and would come to look at the church as soon as she could. Her visit to the church increased her excitement and enthusiasm for the project. And so began a very fruitful relationship in which Beryl Dean and her team designed and made an astoundingly unique set of church furnishings and vestments (many at cost price) which I shall try to describe and illustrate here over the next few weeks.

All Saints, Newland, Gloucestershire: painting of the Virgin and Child and Saints in the St John and St Nicholas Chapel by Eleanor Fortescue- Brickdale

Hanging in the Lady Chapel are the 4 beautiful appliquéd banners shown in this post. These were on no one’s list of essential items but are my particular favourites and, I think, a shot of genius in the way their colours catch the light coming through plain glass windows which makes them act like the absent stained glass itself. Just as lovely are the unexpected glimpses you get of these banners through the arches from all sorts of different spots in the church. They are fiendishly difficult for the amateur to photograph to their advantage. How I should love to view them close up.

The chapel dedicated to St John and St Nicholas to the right of the high altar (after restoration but before the new stained glass)

Just as I was beginning to write this post my husband appeared with a box file full of papers documenting Beryl Dean’s involvement, including letters, a couple of small sketches for the chasuble and larger full scale sketches for the embroidered panels. Sadly, at first glance I could see nothing giving me any more detail about the banners but a quick skim through some of Beryl Dean’s letters revealed a warm person who understood and responded to the some of the many difficulties posed by the unique circumstances of the problematic return of the misappropriated money – including funding for labour and materials she had already paid for herself. The letters also reveal how she dealt head on and diplomatically with some parishioners who were having difficulties with the project. With a little frisson of surprise I noted her address – an Islington square my Uber often takes me past on my way to Paddington. There’s something wonderful about having so often passed so closely by the house where someone you’d loved to have met once lived. More lovely Beryl Dean work next week.

All Saints, Newland, Gloucestershire:The Lady Chapel, the left side with 2 banners (designed and worked by Beryl Dean and her team)

All Saints, Newland, Gloucestershire:the Lady Chapel, the right side, with 2 banners (designed and worked by Beryl Dean and her team)