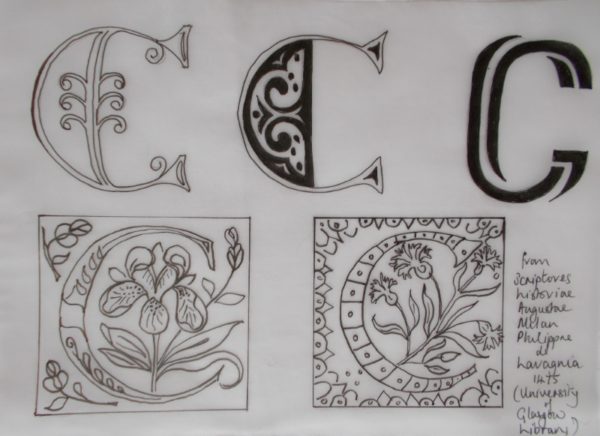

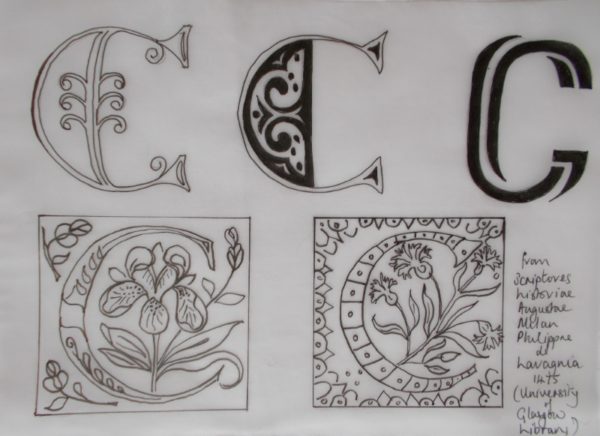

A whitework alphabet: letter C (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

Greatly enjoying the whitework alphabet, I’m finding the limiting of colour liberating rather than restricting. I don’t know, maybe it’s the phase of mind I find myself in – colour for knitting, white for embroidery – it all seems eminently satisfying. This week’s letter was inspired by a beautiful cornflower brooch and it could be said that the embroidery would be improved by the addition of cornflower blue, a particularly lovely shade redolent of summer skies and seaside seas. In spite of that, I stuck to white (Anchor No 1 for the flower sprig and the more yellowy 3865 for the letter C itself).

A whitework alphabet:sketch of letter C (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

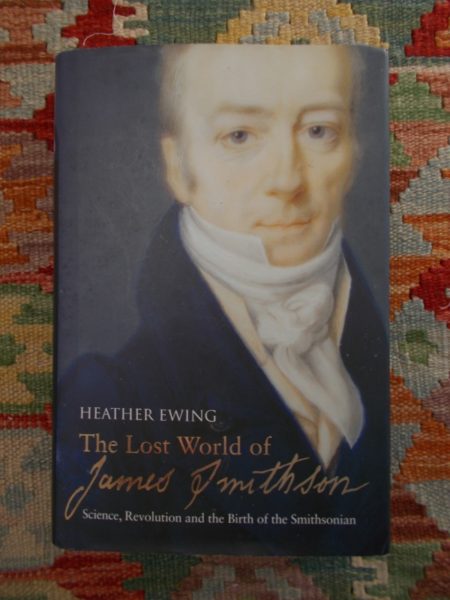

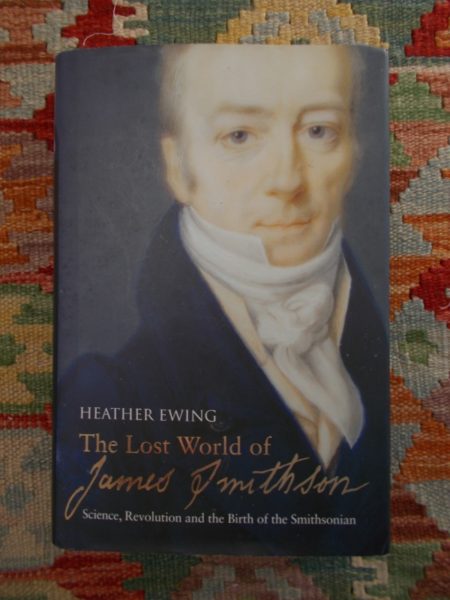

Moving and tidying someone else’s books is not without its benefits, especially if books enter their house as regularly as if they were an item on the weekly shopping list. Rarely do I leave daughter No 1’s house without a borrowed volume or two. Some, like Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends leave me cold and eager to return them (wondering briefly whether to take it straight to a charity shop). Other books, fortunately are gems and tell me about things I never knew I wanted to know about. The dust jacket of Heather Ewing’s The Lost World of James Smithson , Science, Revolution and the Birth of the Smithsonian (pub. Bloomsbury in 2007 ) had me hooked straightaway and, though I can’t say the book gripped me tenaciously all the way through, much about the story she tells is fascinating.

A whitework alphabet: letter C (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

James Smithson was the unacknowledged illegitimate son of a well-born widow, Elizabeth Macie, and Hugh Percy, the first Duke of Northumberland. Being denied his father’s name, James Macie changed his name by deed poll to James Smithson (his father’s family name) when his mother died and determined to make that name “live on in the memory of men when the titles of the Northumberlands and Percys are extinct and forgotten.”

Sketches of various Cs found online

Smithson’s early adult life progressed unspectacularly through Pembroke College Oxford, the writing of scientific papers and scientific discoveries, to being the youngest Fellow of the Royal Society. A Grand Tourist, he visited eminent European scientists and their laboratories rather than artists and art galleries and collected mineral specimens for a formidable cabinet of curiosities. The French Revolution he experienced at first hand – being there when his friend the chemist Lavoisier went to the guillotine. In spite of this he was optimistic about the French and American Revolutions and thought science was the way forward. His great weakness was gambling, though he seemed to know when to quit and was canny in investing what he won – so much so that when he died, he bequeathed (in 1836) a surprised American government 104,960 gold sovereigns (then about half a million dollars) to establish a foundation in Washington “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men”. He had never set foot in America.

Letter C in silk before satin stitch

It seems it wasn’t easy to give America a large amount of money and the unprecedented gift was only accepted after an international lawsuit and a decade long congressional battle. Thirty years later and more problems. Four years into the Civil War, the Smithsonian now just a decade old, alone but prominent in an unfinished Washington cityscape, suffered a terrible fire. Workmen were hanging a collection of paintings of native Americans (overlooked by a copy of the statue of the Dying Gaul accompanying the paintings to suggest parallels between ancient vanquished people and these noble native peoples now being annihilated in the push west across the continent). Temperatures so low that water had frozen in the fire buckets caused the workmen to bring a stove into the gallery and attach it to what they thought was a flue in the gallery wall but which was just an unfortunate hole in the wall. The ensuing fire completely destroyed the gallery and the offices, including all the papers and effects of James Smithson, and what was almost worse, (a lesson to museum curators everywhere) there was no inventory – no one had found the time.

Heather Ewing’s The Lost World of James Smithson

Smithson’s papers gone the body was next threatened with extinction as the Genoan cemetery where it lay was condemned and marked for destruction. On New Year’s Eve 1903, the story goes Alexander Graham Bell and his wife exhumed the body in the middle of a blinding snowstorm and had it brought to the Smithsonian. After an uneventful rest of 70 years, in 1973, Smithson’s body was exhumed once more and yet again tragedy struck as blowtorches used to melt the solder on the coffin set alight the silken lining. Nearby fire extinguishers would have further damaged the bones so workmen ran back and forth to a water fountain, using their mouths as make shift water carriers! Reading about these disasters I can’t help but think, for perhaps the first time, what a brilliant idea making risk assessments is.

So, with little remaining material, Heather Ewing set about trying to piece together Smithson’s life. A modern researcher, she knew history can be gleaned from student registers, guest lists, probate records, passport controls, bank records and book marginalia, as well as papers and diaries of those who knew or were related to him. From these she has helped pull the man from the shadows – a little but just not enough.