Fair isle cardigan 3-6 months (pattern Debbie Bliss Baby Cashmerino, 2002)

Another new baby provides the perfect excuse for just the right sort of knitting – a bit of Fair Isle, not to much plain knitting and no lengthy seams. I did agonise a bit about the Fair Isle design, not wanting to overwhelm a tiny person with the sort of big bold pattern I have my sights set on at the moment so the resulting cobbled together design for the yoke is a bit underwhelming, but I think it has a certain charm.

Fair isle cardigan 3-6 (pattern Debbie Bliss Baby Cashmerino, 2002

Pink buds of apple blossom are waving gently outside my window and I’m determined to enjoy this bit of the ancient tree’s largesse before those little twists of pink loveliness give way to the apple grenades that bombarded us so ferociously last August. Plants and plantsmen have been much on my mind since Christmas when I received the happy gift of Victoria Johnson’s book American Eden about the almost completely forgotten Dr David Hosack, who set up New York’s first public, non commercial botanic garden and who, until this book came out was probably better known for his brief appearance in Jon Lin Manuel Miranda’s rap musical Hamilton. Good friend of both Hamilton and Burr, he attended the 1804 duel in his medical capacity, cared for the grievously wounded Hamilton until he died the next day but carried on a lengthy correspondence with Burr during his self imposed exile abroad in 1808 after the latter’s subsequent acquittal in a treason trial. Some of my family have been to see the musical and enjoyed it greatly. Not a fan of rap, I’ve watched what’s available on YouTube and been surprised at how much I’ve enjoyed it too, but then again, Miranda did co-write songs for Disney’s Moana, so he’s not a man with a tin ear! Hosack, a man with a medical bag, is given no words in the musical but just before the duel takes place is referenced in the following lines:

“Hamilton: You pay him in advance, you treat him with civility.

Burr: You have him turn around so he can have deniability.”

Fair isle cardigan 3-6 months (pattern Debbie Bliss Baby Cashmerino, 2002

An Enlightenment man in the European mould Hosack sailed to Europe in 1792 to complete his medical studies. In Edinburgh he realised how limited was his knowledge of medicinal botany, so he moved to London (the capital of both botany and anatomy) where he attended a private medical school in parallel with learning from the botanist William Curtis at work first in his Brompton Botanic Garden and then in the garden we have come to know as the Chelsea Physic Garden, spending as much time in the garden and greenhouse as in the lecture theatre. Curtis cultivated American species in ever greater numbers and Hosack began consider the potential botanical richness of the vast American wilderness beyond the East Coast settlements. In 1796 he returned to America where he established himself as a doctor and devoted family man.

Fair isle cardigan 3-6 months (pattern Debbie Bliss Baby Cashmerino, 2002

Botanical interest never lapsed. He set up and was the first president of the New York Horticultural Society with Adams, Jefferson and Madison as founding members. This was not enough for a man of vision and prodigious energy and in 1801 he bought land beyond the city for a botanic garden to be devoted to the study of indigenous plants. 4 miles from his Broadway home, getting to the land with men and equipment was a major expedition but he persevered, irrigated the site, brought it to productivity and built huge glass houses for the study of plants of tropical temperament from hotter parts of the country. For too few years medical students studied alongside botanical researchers, observing, classifying and trialling. But such an enormous endeavour could only gorge on money and Hosack’s own purse was nearing empty. Promised funding from public bodies materialised too late and was anyway too little – considerably less than Hosack had paid for the land, with no consideration for value added from cultivation, building and the stock of plants. New York State bought the land in 1810. In 1812 marble slabs were placed along the Middle Road – the beginnings of the grid system later to characterise New York’s street plan. The Middle Road became Fifth Avenue. The land was made over to Columbia College in 1814 and garden and buildings fell into decay and dilapidation as the university had no interest in such botanical pursuits. In the 1920s the land was leased to John D. Rockefeller Jr. Today it is the site of the Rockefeller Center, so when you go for a winter skate on the ice rink there, try to imagine being out in the country with no skyscrapers just a few greenhouses and greenery as far as the eye can see. Radio City Music Hall was built over the footprint of Hosack’s conservatory. On a low wall in Channel Gardens hangs a plaque in memory of Hosack and his garden. sic transit gloria mundi – again (or rursus in Latin).

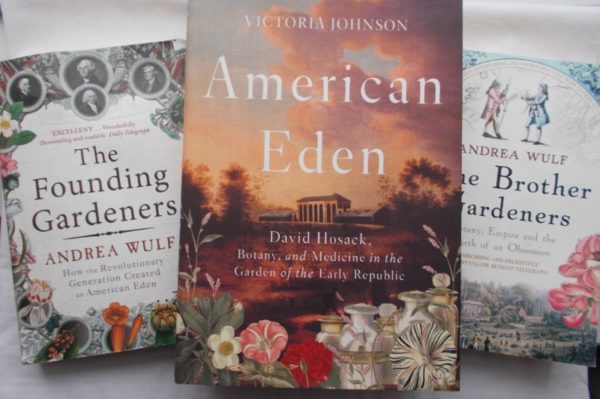

Pioneering American gardening: Andrea Wulf, The brother Gardeners 2008; Andrea Wulf, The Founding Gardeners, 2011; Vicoria Johnson: American Eden, David Hosack, Botany and Medicine in the garden of the Early Republic, 2018

In 1816 Hosack was made an FRS (Fellow of the Royal Society) – a fully fledged fellow and not just a foreign member – a rare accolade. Two wives and two children pre-deceased him but he found happiness – and wealth! – with his third wife. With her he bought a Hudson River Estate and established his second botanical garden which gave meaning to his final years.

Andrea Wulf’s two excellent books on American gardeners The Founding Gardeners and The Brother Gardeners are remarkable for containing no mention of Hosack. Wulf herself has praised Victoria Johnson’s book and her research into this forgotten man, which just goes to show how easy it is to slip between the cracks in the floorboards of history. I’ve blogged about Wulf’s books here and, loved them – having read them twice, I know I will read them again, as I shall with Victoria Johnson’s American Eden, and I shall do it with a great vernal sigh of pleasure.