Embroidered T shirt sleeve (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

I do very little embroidery for myself but after I finished the children’s Christmas T shirts, I suddenly had the fancy of doing a bit of decoration on the much neglected sleeve bottoms of a few new T shirts. Not a lot of space to get carried away over, I thought, but then, like Topsy the embroidery just grew and grew and was more embroidery than I’d anticipated. I’ve possibly let my stitching go too far up the arm so that what I at first imagined being subtle decoration has now become de trop. We shall see.

Embroidered T shirt sleeve (hand embroidered by Mary Addison)

design for T shirt sleeve

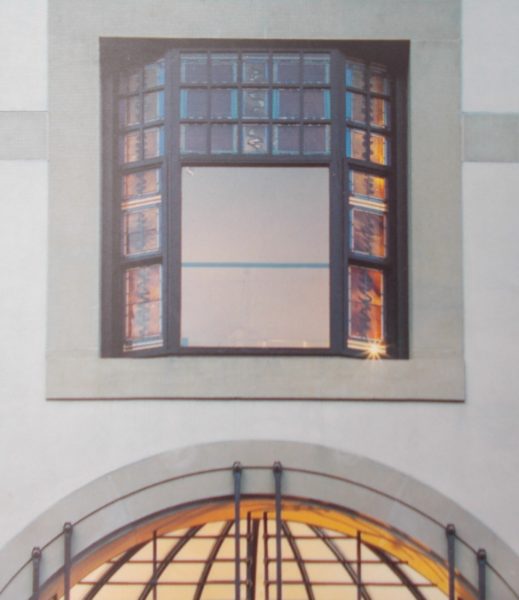

Meanwhile The Wilson, Cheltenham’s unhelpfully named art gallery and museum, is still closed, supposedly for a certain amount of remodelling internally, although we regularly have cause to go past it and have yet to see signs of any sort of constructive activity. Well, that’s not quite true for one day there was a scaffolding tower (bereft of workers) which caused us to look up and then we noticed the window on the Hugh Casson front of 1989 looking very sad. The quirky stained/painted glass panels commissioned and handmade for the new extension were visibly cracked, broken, missing in places and some had suffered the even worse indignity of being blocked up with what looked like bits of old cardboard. When we went past the art gallery the following week, it was clear that all individual panes of glass that once flashed zigzags of warm yellows and orangey reds when the room behind was lit up had been replaced by undistinguished pieces of clear modern glass. The glass had never been an enormous in your face sort of feature but the lack of such detailing has diminished the look of the whole front, much as a once elegant and stylish outfit is never quite the same when distinctive buttons are lost and replaced by department store basics. Woe. Experience suggests, make-do repairs very often become permanent.

The Wilson/Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum Sir Hugh Casson extension 1989

But The Wilson is not forgotten in my husband’s art appreciation sessions at Chapel Arts for he likes to show images from Cheltenham’s collection and, thanks to Art UK, the charity and online home for oil paintings in every public collection in the UK, he can do this quite easily. Since 2003 Ark UK has digitised over 280,000 paintings and all are now available just a few keyboard taps away. And of course, the really great thing about an online depository is that you have access to all those paintings which would otherwise live hidden lives secreted away in museum stores and dusty basements. (Bendor Grosvenor’s programme ‘Britain Lost Masterpieces’ is in part based on his trawling such minimally frequented depths with a connoisseur’s eye and choosing paintings which he thinks merit further consideration. His success rate is impressive and additionally his researches make for some of the best of television viewing of the visual arts.)

The Wilson/Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum: Sir Hugh Casson extension 1989: detail of first floor window

It’s always a joy to come upon women successful in their chosen fields and even more so when they lived in a historical past littered with more obstacles, prejudices and domestic commitments than we would find fair today. The Dutch painter Rachel Ruysch (1665 – 1750) is one of these special breeds of women. The Wilson is fortunate to have a portrait of her and also one of her still lifes which genre she specialised in. Women painters of this period often concentrated on still lifes for practical reasons for flowers were easy to come by. As Rachel’s father was a professor of anatomy with interests in botany, his collections of botanical specimens were an additional source of inspiration. Rachel assisted her father in preparing specimens for the collection and producing botanical studies showing plants in the various stages of life. She later even taught her father and sister how to paint flowers accurately. From such work, still lifes became a natural progression. As with other practitioners of the genre, her paintings are a sort of theatre for flowers, complete with dramatic effects. Gorgeous blooms bustle together regardless of seasonal flowering. Peonies of May and poppies of full summer nod their heads between branches of spring blossom and wayside weeds while the odd leaf of a distinctly overblown cabbage contrasts nicely with the soft petals of a drooping rose. Close up and lushness visibly tips into decline – dry leaves curl and discolour with age, disease or infestation by insects. Lighting is spectacular in its artifice hitting bunches of flowers face on, then picking out the odd petal or stem here and there; the background, like the backdrop in a theatre is sooty black to enhance those glorious flowers.

Schalcken, Godfried; Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750); Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/rachel-ruysch-16641750-62014

Rachel was very successful and utterly in tune with the taste of a time when the burgeoning middle class were building their elegant canal side houses and in need of paintings of the right size to sit on either side of their fireplaces. At a time when Rembrandt was earning something like 500 guilders for a painting, Rachel was getting 750-over 2,000 guilders. And if that’s not impressive enough, she did all this and gave birth to 10 children too. Fortunately she was married to a fellow painter who seemed to appreciate her work. There is a lovely painting she did of both of them with one of their children. She is looking directly yet languidly at the viewer, while her husband stands behind her with one hand on her shoulder and the other pointing somewhat proudly at a painting on an easel. The child has eyes only for her mother to whom she is offering something, while the not very maternally looking mother seems to be somewhere else entirely!

Ruysch, Rachel; Flowers in a Glass Vase; Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/flowers-in-a-glass-vase-62007

In 1722 the family won the lottery. Today Rachel Ruysch is largely forgotten. Sic transit gloria mundi.