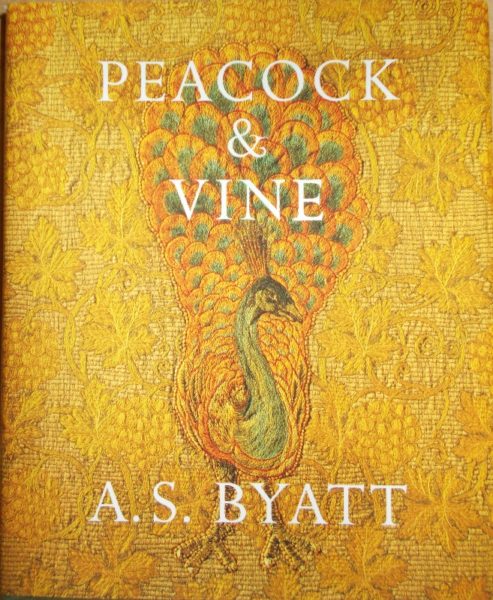

A.S.Byatt: Peacock and Vine (Chatto & Windus, 2016)

Enveloped in a warm and slightly light headed feeling after visiting the May Morris exhibition in Walthamstow earlier this year, and, impressed by the range of books so small a museum shop had to offer, I came away with a small pile of rather wonderful reading matter, one of which was this beautifully produced little book by A.S.Byatt. Published in 2016, I’d never noticed it in shops before and, with a subject matter of both Morris (William) and Fortuny, born almost a century apart and as I thought about as different as two men could be, I was hooked.

Fortuny logo; frontispiece to A.S.Byatt’s book ‘Peacock and Vine’ (Chatto and Windus, 2016)

The tone is set straight away in the first line of the book, so I shall quote it in full;

Fortuny logo taken from Fortuny blog

“We were in Venice in April and I was drunk on aquamarine light. It is an airy light, playing with the moving dark surfaces of the canals, shining on stone and marble, bringing both together in changing ways, always aquamarine. I found that an odd thing was happening to me. Every time I closed my eyes – which I increasingly did deliberately – I saw a very English green, a much more yellow green, composed of the light glittering on shaved lawns, and the dense green light in English woods, light vanishing into gnarled tree trunks, flickering shadows on the layers of summer leaves.”

Fortuny logo from A.S.Byatt’s ‘Peacock and Vine (Chatto and Windus, 2016)

Caught up in this visceral trembling, Byatt pulses on with overly creative zeal to compare (and occasionally contrast) these two unique individuals until I too started to make wild imaginings – William, somewhat scruffy in a ill fitting three piece suit, finds himself trapped and wrapped about in the pleated folds of a Fortuny Delphos dress while Mario, impatiently Italian, struggles to be free of all too realistic scrolls of acanthus leaves, thorny roses and nesting birds, while fighting to hold on to his brocaded turban! I go too far but in many ways this is a book luxuriating in diverging and colourful threads of thought – the publisher indulgently seems to have given the writer 180 blank pages to do with as she will. But scrape away the hyperbole and beneath it lies the primacy of craft – the coming together of ideas and skills to produce things that increase human well being, if not actual happiness.

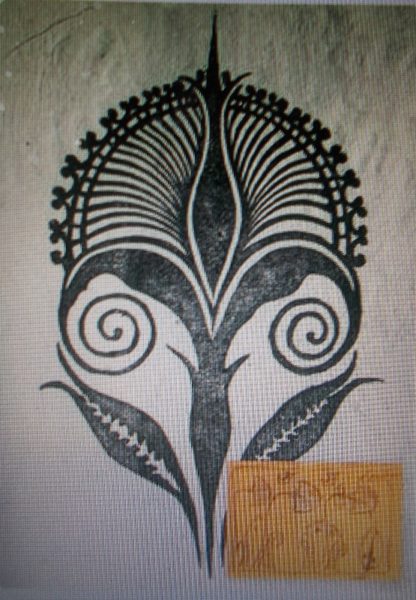

William Morris; taken from A.S.Byatt’s “Peacock and Vine (Chatto and Windus, 2016)

As Byatt has got older she has admitted to becoming increasingly interested in craftsmen – perhaps partly because she can trace her ancestry back to Staffordshire and the pottery industry. For both Morris and Fortuny, hand crafting was primary. Morris set up the Merton abbey Works while Fortuny employed up to 100 artisans in his Venetian palace. Fabric designs of both men were lavish celebrations of overblown flora and fauna, though Morris’s fauna tended to be of a garden variety while Fortuny’s inclined to the fantastical. Domestically, however, they were at opposite poles. Fortuny, the aristocrat, married a beautiful French divorcée and though inhabiting a world of seductive elegance and superficial plenty, their relationship, including working together, survived. Morris married lowly born Janey and suffered the heartbreak of sharing her with Rossetti; the marriage was a far from a smooth ride.

William Morris vignette (taken from A.S.Byatt’s “Peacock and Vine” (Chatto and Windus, 2016)

A curious coupling, I found the Fortuny bits the more interesting, probably because I already knew more about Morris, an English icon. There are some surprising similarities between the two craftsmen/entrepreneurs but their differences are many. I would really had preferred it if the whole of the book had been devoted to Fortuny, of whom I would like to learn more, but perhaps that misses the point, for in the end I realise the book is as much about Byatt and the urge to create as it is about Morris and Fortuny.

Fortuny logo; taken from A.S.Byatt’s “Peacock and Vine (Chatto and Windus, 2016)

The book is well illustrated but I particularly love the little vignettes at the end of chapters – great inspiration for embroidery!